One of my favourite interviews ever was with Hugh Wilson. The Florida native just sounded like fun on the phone, and generously shared his memories of creating and working on a show I adored in my college days, WKRP in Cincinnati.

One of my favourite interviews ever was with Hugh Wilson. The Florida native just sounded like fun on the phone, and generously shared his memories of creating and working on a show I adored in my college days, WKRP in Cincinnati.

Sad to report, that Wilson passed away last Sunday at his home in Charlottesville, Va. He was 74.

Now considered a comedy classic, WKRP in Cincinnati (1978 – 82) was about a small market rock ‘n’ roll radio station struggling to stay alive in the disco era. The comedy, in fact, barely survived its first season. What saved it, according to the man who created it, was Canada.

“When the show first went on,” Wilson told me, “it was struggling in the ratings in the U.S., but the ratings in Canada were great right from the beginning. I’ve never understood that but I’ve always been super grateful for it.”

Wilson would go into meetings with U.S. network officials and point to the success in Canada “as part of my plea to keep us on the air.” It worked for four seasons and 90 episodes.

advertisement

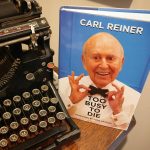

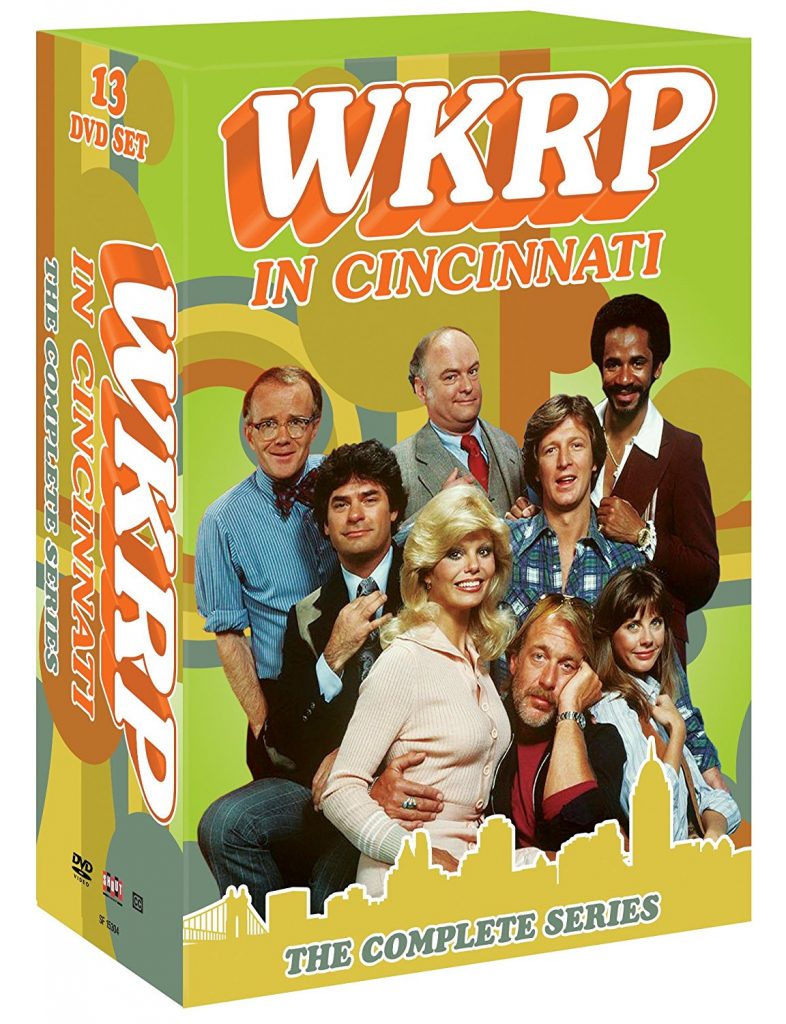

A little over three years ago, I spoke with Wilson upon the release of WKRP in Cincinnati: The Complete Series, a 13-DVD box set. The handsomely-produced box set was held up for years until Shout! Factory untangled the legal mess behind most of the many music clearances. (Pink Floyd was among a handful of hold outs).

A little over three years ago, I spoke with Wilson upon the release of WKRP in Cincinnati: The Complete Series, a 13-DVD box set. The handsomely-produced box set was held up for years until Shout! Factory untangled the legal mess behind most of the many music clearances. (Pink Floyd was among a handful of hold outs).

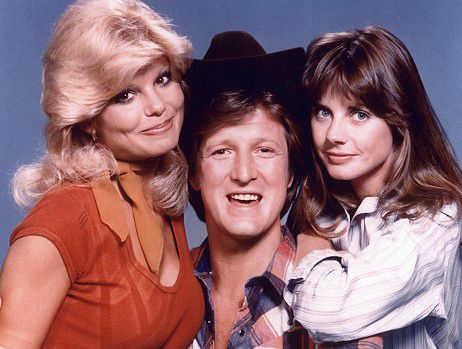

Wilson, in fact, thought he had struck gold and would never have to work again after WKRP left CBS and went into syndication in 1982. The comedy, which starred Loni Anderson, Howard Hesseman, Gordon Jump and Tim Reid among a stellar comedy ensemble, became a bigger hit in reruns than in broadcast, more popular at first than Mary Tyler Moore, The Bob Newhart Show or any of the other MTM hits.

“It was like owning a little oil well,” said Wilson. When the WKRP syndication money started rolling in, he ditched Hollywood and moved his family to a farm in Virginia. “I had decided incorrectly I didn’t have to work,” he told me. “Soon after, the WKRP oil well money stopped.”

What actually stopped was the music. WKRP had a complicated history of music rights restrictions. Music from Elvis Costello, Bob Dylan, Elton John, Stevie Wonder, The Who, Neil Young, Paul McCartney and Wings, The Police and The Rolling Stones was featured on the show.

As the music deals expired, songs and episodes had to be pulled from the WKRP rerun rotation. Sound-a-like songs were plugged in over time, but the watered down series fell out of favour.

How Wilson stumbled into the business is a story worthy of its own series. He was working in advertising in Atlanta and hating it when he called up an old pal: Jay Tarses (who went on to create some ahead-of-their-time shows himself, such as The Days and Nights of Molly Dodd, and Slap Maxwell).

Tarses was able to get Wilson an interview at MTM, with none other than legendary executive (and Mary Tyler Moore’s husband at the time) Grant Tinker. The two hit it off, but since Wilson didn’t have any writing credits, the best Tinker could offer was an intern position on one of his sitcoms, The Bob Newhart Show. Wilson grabbed it.

“Since nobody would ask a 30-year-old intern to make coffee,” Wilson told me, he had plenty of time to roam the studio. Most of the MTM comedies in the `70s were shot on what is now known as CBS Radford. It was on that storied lot where Wilson cut his teeth on the TV business. He was able to spend hours observing the classic MTM comedies being crafted from the studio floors and rafters and eventually landed a gig as a writer on The Bob Newhart Show.

“Since nobody would ask a 30-year-old intern to make coffee,” Wilson told me, he had plenty of time to roam the studio. Most of the MTM comedies in the `70s were shot on what is now known as CBS Radford. It was on that storied lot where Wilson cut his teeth on the TV business. He was able to spend hours observing the classic MTM comedies being crafted from the studio floors and rafters and eventually landed a gig as a writer on The Bob Newhart Show.

Wilson recalls the warmth and inclusion he felt from Newhart and co-star Suzanne Pleschette but says he learned even more from the star of his next series, The Tony Randall Show. Stage and screen veteran Randall stressed motivation, telling Wilson every character should always know exactly why they were entering a room.

In 1978, when WKRP began, it became MTM’s first videotaped comedy. This was mainly a cost cutting measure. Not so much because videotape was cheaper than film, but because, for some reason lost to history, the music rights clearances for the rock tunes played on the sitcom would be half the cost if the series was taped.

The decision to go video moved the series off the usual Studio City MTM lot and down into Hollywood. The Radford lot simply wasn’t set up for video. Large “side vans,” basically portable control centres, were trucked next to the sound stages for the occasional video production. In Season Two, once MTM was fully equipped to handle video production, WKRP moved back and Wilson says he was deeply honored to shoot his series in the same soundstage where Mary Tyler Moore was filmed.

Still, being “off shore,” as Wilson calls it, that first season, probably added to the sense of creative freedom Wilson says he found at MTM. WKRP, as commentary on the DVD box set reveals, was a pretty free-wheeling show. It helped, Wilson is quick to point out, that Tinker was there to protect the novice showrunner from the network.

“I was lucky I was at MTM,” acknowledges Wilson. Tinker ran interference. “I don’t know how he did it—he was a perfectly charming man is probably how he did it. He probably reminded them that four of their top 10 hits was from him. He would come back and say, ‘Hugh, it’s all right, you can do that.”

“I was lucky I was at MTM,” acknowledges Wilson. Tinker ran interference. “I don’t know how he did it—he was a perfectly charming man is probably how he did it. He probably reminded them that four of their top 10 hits was from him. He would come back and say, ‘Hugh, it’s all right, you can do that.”

Not every battle would be won. One thing the network would not tolerate in 1978 was any drug references, even thought it was obvious, says Wilson, that Hesseman’s Dr. Johnny Fever had, well, issues. “I would sometimes have him stepping out of a closet waving his hand as if to clear the smoke,” says Wilson of his scripts. The network censors would insist that those scenes be cut. Soon it became a strategic game for Wilson. “I knew they were going to get it but I would pretend to be all offended and they would give me something else.”

Wilson says the weekly production schedule would go something like this: “We’d sit sown and read the script on Monday,” he says. “In the beginning the scripts were pretty tight. By the third year, we almost had blank pages, we were so far behind.”

That’s pretty evident if you look at the DVDs of the series. Things seem to go off the rails in Season 3, with bizarre one-offs and extended dream sequences. Part of my fascination with the series, besides Anderson and Jan Smithers (equally beguiling in a non-actor-y way as Bailey Quarters) is how experimental and un-polished it often looks.

Wilson said that the cast had faith that the show would be there by Friday. Some of the more seasoned improvisers, such as Hesseman (weaned on the California comedy troupe The Committee), were given a great deal of freedom to fashion their own dialogue within a scene.

Two versions of each episode were committed to tape each week. One with, and one without an audience. “I found that if you brought in an audience during the day, around 4 or 5, that audience would take you down,” says Wilson. “If you brought in an evening audience, they were so excited to be there.” After a few weeks Wilson turned away the afternoon audience. “We’d shoot the show dry and the I’d be there yelling, ‘Energy, have fun, smile.’”

Separating the two shows seemed to spark the cast. “Boy, when that live audience came in, and they started getting the laughs, the actors started just having so much fun with it.”

Wilson says the studio audience tapings were done very quickly. Audiences came in at 7 p.m., “we fired through the show” and were back on the street by 8:30. Wilson knew he already had an earlier taping, without an audience, in the bank, so any mistakes made in front of the fans in the bleachers could be quickly patched later.

Wilson did the warm up himself. “I wasn’t about to let some comic come in there that didn’t know the show.” Wilson would occasionally drag cast members before the studio audience with him. “If I knew Gordon [Jump] wasn’t in the next scene, I would bring him out to do a two-hander with me while we re-set. I’d ask him his questions, he had his shtick everybody had their shtick.”

Doing a four camera, studio audience sitcom in 90 minutes is pretty much unheard of. Three hours is considered pretty good. Some went way longer.

“We’d hear about Laverne & Shirley shooting until two in the morning,” says Wilson. “I thought that was just toxic.”

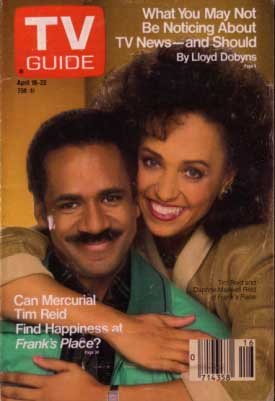

Wilson went on to do another CBS series with Tim Reid that was probably HBO before HBO: Frank’s Place (1987-88). Set and shot in New Orleans, it was uneven but ground-breaking in slice of African American life not seen in North American television at the time. It would also have fit in well with the more serious comedies in favour today.

Wilson could do slapstick; he co-wrote the first “Police Academy” movie with Pat Proft. He created Jon Cryer’s early sitcom The Famous Teddy Z and tried to revive WKRP in 1991 – 93 with some of the original cast members.

Wilson could do slapstick; he co-wrote the first “Police Academy” movie with Pat Proft. He created Jon Cryer’s early sitcom The Famous Teddy Z and tried to revive WKRP in 1991 – 93 with some of the original cast members.

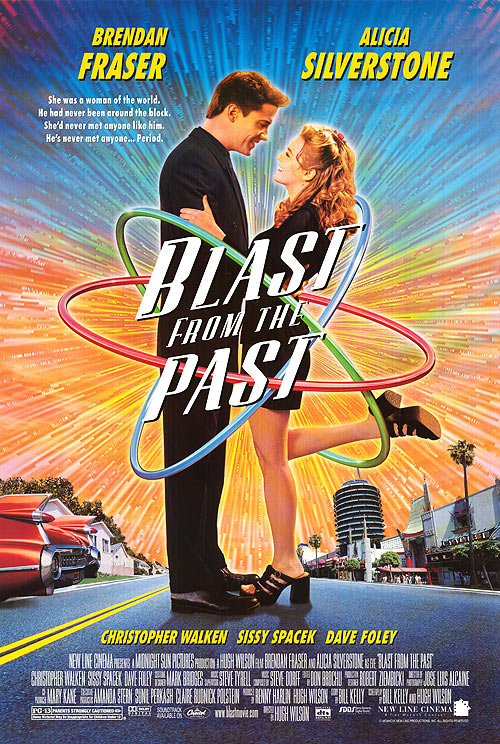

Last week in Pasadena, on the just concluded TCA press tour, Wilson’s name came up again. I was talking with Brendon Fraser — at TCA to promote two TV projects, Trust and Condor. I bring up one of my favourite Fraser flicks, “Blast from the Past” (1999). Who wrote it? Hugh Wilson. “I believe it was based on his own experiences growing up with a bomb shelter in his backyard,” the actor explained.

Is that true? What I wouldn’t give to call Wilson up and do a little fact checking. Condolences to his family, friends and anyone else who can’t get that WKRP theme song he co-wrote out of their head.