In 1982, I was invited to a private dinner with Norman Jewison.

Memories of that encounter flooded back on the news this week that the dean of Canadian film directors had passed away Saturday at 97.

Forty-two years ago, he had accepted an invitation to be a guest lecturer at the University of Toronto. The chairman of the Film Department at the time, Professor Gino Matteo, knew I used to draw the editorial cartoons for the U of T’s paper, The Varsity. He asked me to draw a caricature of the filmmaker so that it could be presented as a gift. I was thrilled to get the assignment.

Jewison has a farm north of Toronto so I drew him raising a crop of film reels, one for each of his features to that point.

By then I had seen and admired many of his films. I was way too young to appreciate Jewison’s Best Picture Oscar winner “In the Heat of the Night” when it came out in 1967. Saw it I did, however, on the big Drive-In screen in Orangeville, Ont.

My parents were friends with the family that ran that long-gone outdoor cinema. We must have gotten in for free as my dad took us there quite a bit. Even thought I was barely ten-years-old, the racial confrontation between Rod Steiger’s Southern police chief and Sidney Poitier as Virgil Tibbs was raw and impactful.

advertisement

More fun years later was discovering “The Russians are Coming, The Russians are Coming,” “The Thomas Crown Affair,” “Moonstruck” and many other Jewison gems, each so different than the last one.

Matteo taught Film Studies and English at U of T and allowed me and high school pal and comedy club partner Pat Bullock to earn a credit by making a short comedy film. It ended up winning the top prize at Telefest, an Ontario university student film competition.

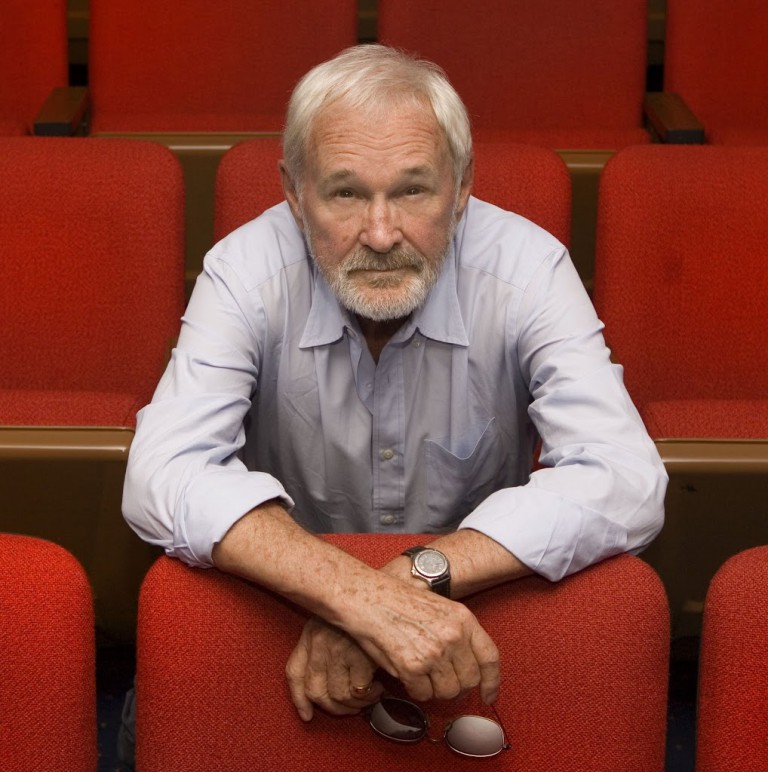

That was a first for U of T. Matteo the mentor, who passed away at 83 in 2021, was rewarding me for the caricature, but he was also generously sharing an opportunity to sit with one of the top filmmakers in Hollywood. It was an informal, two-hour masterclass on filmmaking and humanity on the top floor of the Park Plaza hotel.

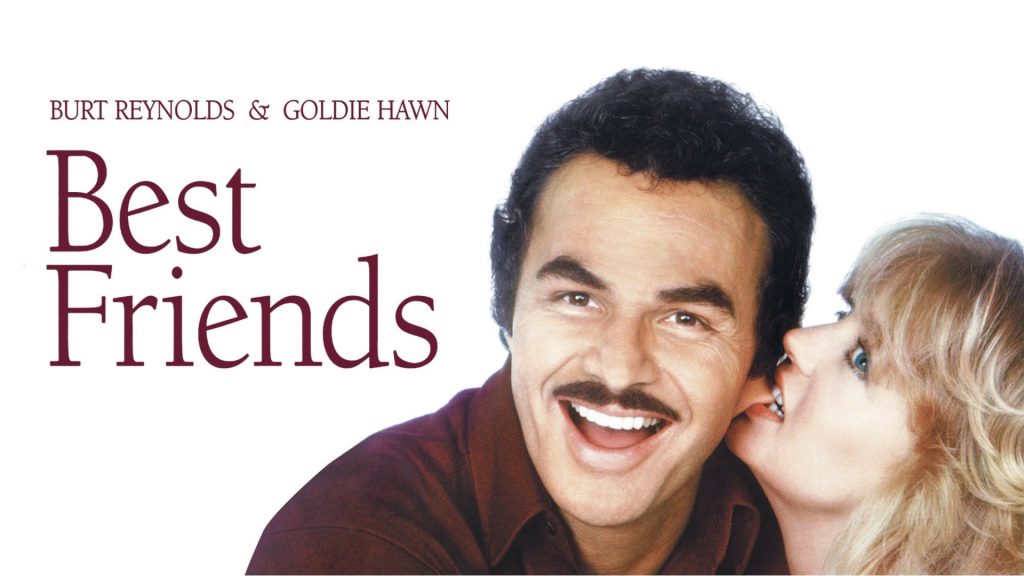

Jewison’s latest release was a minor work, a romantic comedy titled, “Best Friends” starring Burt Reynolds and Goldie Hawn. I had seen it, and complimented Jewison on drawing a relatively unmannered performance out of the “Smokey and the Bandit” star. Jewison confided that, after a few takes filled with Reynolds’ usual eyebrow wiggling and other mugging, the director pulled the action star aside and asked him to save all that good stuff till the end of every take.

Then Jewison simply cut it all out.

His overall advice to me, an aspiring filmmaker, was to stay the hell away from film schools.

“Drive a cab until you’re at least 30,” he urged. Live life. Go out and get a variety of experiences before you ever dare to try to tell stories on film.

It was good advice, but without Jewison’s drive and ambition, not to mention his sense of story, well, sometimes life experience can get in the way.

The Toronto native’s rise to the top of his profession is well documented in Ira Wells’ excellent 2021 biography “A Director’s Life.” (Listen to my podcast conversation about this book with the author here.)

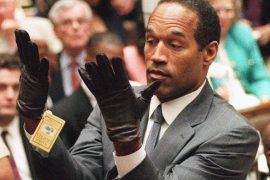

Wells, who worked three years on the book, goes through Jewison’s diverse catalogue, including “Fiddler on the Roof,” “Rollerball,” “A Soldier’s Story” and “The Hurricane.” He examines the director’s early days at the CBC in Toronto as well as directing superstars such as Judy Garland and Harry Belafonte in American television. He addresses Jewison’s passion for mentoring the next generations of filmmakers with the Canadian Film Centre, as well as his commitment to Civil Rights and social justice.

He writes that Jewison’s 24 feature films — 15 more than Quentin Tarantino — “could just as easily have been a dozen, or three or none.” Landing the next film deal, despite all the accolades, never got any easier. It helped that behind Jewison’s nice guy, all-Canadian persona, beat the heart of a lion. As Burt Reynolds once mused, “He must be able to kick the shit out of people in meetings.”

Jewison’s other talent, Wells writes, was to be the director he needed to be in relation to the talent at hand. He could be, as Wells describes him, “a nurturing father figure, a wise older brother, on old fling.” Sometimes he was all three on the same film, as he was on the set of “Agnes of God.”

You could always find Jewison every September during the Toronto International Film Festival on the stony deck of the old E.P. Taylor Windfield Farms Estate — the home for many years of the Canadian Film Centre. His address to the film students in the crowd were always a high point of the event.

At one of these gatherings, I could hardly wait to tell him that I had hunted down and bought on eBay, for the incredibly low price of thirty dollars, a 16mm print of his first feature film — “40 Pounds of Trouble.”

It starred Tony Curtis, who was so impressed with Jewison after working with him on a TV special that he pushed for the film rookie to helm the 1962 feature. The film also stars Suzanne Pleshette, Larry Storch and Phil Silvers. At one point, the cast scrambles across what was then the relatively new Disneyland theme park in southern California, a spirited sequence Jewison basically improvised on the spot after Walt Disney himself gave permission (at a price) to shoot on the grounds.

Jewison’s two word response when I told him I had bought the film? “Burn it!”

Never. It is a sweet, charming little movie, one of Curtis’ most natural and sympathetic performances.

I was able once, at a TCM evening event during a Television Critics Association press tour, to ask Curtis about “40 Pounds.” He didn’t say much about it, but did express regret that Jewison had never cast him in one of the director’s later successes.

Jewison winced a year or so later when I told him what Curtis had said. Could Curtis have played John Mahoney’s part in “Moonstruck”? Perhaps, but Mahoney nailed it and Curtis, the former heart-throb, might have pulled audiences out of those scenes. I got the sense Jewison tried to repay Curtis but, timing, circumstances, or just the need to cast the right actor in the right part — it just never happened.

Another time I spoke with Jewison at Toronto’s Tiff Lightbox Theatre. An upstairs exhibit space and library area had been dedicated to the memory of television interviewer and film historian Brian Linehan. I saw Jewison and his wife Lynne St. David reluctantly edging towards the elevator in order to reach the reception on the third floor. That’s when I learned that Jewison, he with the heart of the lion in the boardrooms of Tinseltown, was afraid of elevators!

I think I started talking about “40 Pounds of Trouble” again, enough to distract the great director. Before we knew it we were on the third floor.

Maybe Jewison’s fear of heights has something to do with a hair-raising incident that occurred during the making of the 1966 feature, “The Russians are Coming, The Russians are Coming.” Jewison gave Carl Reiner his one and only leading film role in the Cold War comedy. In his 2014 memoir, “I Just Remembered,” Reiner writes of the time he, his co-stars Eva Marie Saint and Brian Keith and Jewison all crammed into a four-seater Cessna — along with a fifth passenger, the pilot — on a wild, rainy-night ride north of San Francisco. It all could have ended very badly, but only a pair of boots were lost when the plane eventually landed.

Reiner once described Jewison to me as “his favourite Canadian.” Not just for casting him in a feature, but also for the gifts from his farm Jewison used to ship every Christmas.

Another actor making his film debut on that picture was Alan Arkin. His eyes sparkled at the mention of Jewison’s name when I spoke with him in 2019 during a press session on the set of The Kominsky Method. That’s the Netflix series that paired Arkin with Michael Douglas.

“I have a soft spot for Norman Jewison,” says Arkin. “Working with him was a dream. There was no way for it to be a better experience than he made it. He turned the whole town into a family, the whole town of Fort Briggs, California.”

Arkin, who passed away last June, says the entire actual town would be invited by Jewison to join the cast and crew to screen the dailies every night.

“Where have you ever heard anything like that? It was an extraordinary experience.”

I got a similar reaction from others at the mere mention of Jewison. To me, he’s always been more of a six degrees of separation hub than Kevin Bacon.

One time I was interviewing Faye Dunaway in the backseat of a car on her way from the set of her Canadian acting gig (guesting on CBC’s The Road to Avonlea) to the Toronto airport. It was the only way she would do the interview, take it or leave it.

We quickly hit traffic as well as the interview wall. When I asked her to share memories of working with Jewison on “Thomas Crown,” however, she was immediately re-energized. I thought she was going to stop the car and demand we search for his Yorktown production offices.

Well into his nineties, Jewison continued to speak at other Canadian Film Centre festival gatherings. He talked about how famed Canadian-bred Kentucky Derby winner Norther Dancer used to frolic on the Windfield Farms grounds. The director pointed out that Queen Elizabeth once slept upstairs at the secluded estate, now the main CFC headquarters. The Queen, according to Jewison, loved the ponies.

Jewison, who founded the centre in 1988, saw the annual film festival event grow from a humble industry barbeque to a spectacular cultural success story. In its 37th year, the CFC boasts close to 2000 alumni with a focus today on providing opportunities to a diverse group of storytellers.

“This place has grown and flourished beyond my wildest dreams,” Jewison told the industry crowd assembled at the last gathering I attended in 2022.

He was 96 at the time, ever impressive if finally showing some evidence that he was well into the final reel.

His main message, as it was to me all those years ago, was always directed to “all the young filmmakers out there.

“I just can simply say, find a good story. Just tell stories that move us to laughter and tears, and maybe reveal a little bit of truth about our selves.”