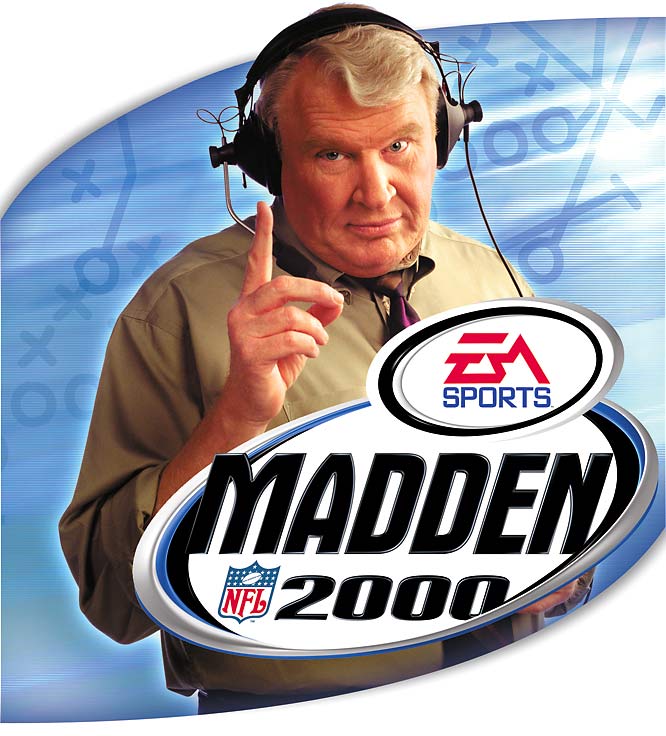

A few years ago, my son Dan was shocked to learn that there really was a John Madden.

To many under 30, Madden — who died Dec. 28 at 85 — is more likely thought of as Col. Saunders or Ronald McDonald, a corporate brand ambassador. If you are closer to 50-plus, you remember the Minnesota-native for who he was, an NFL Super Bowl-winning coach who had a spectacular second Act as a network football analyst.

If you’re somewhere in-between, you might remember him as a guest host on Saturday Night Live, the guy who gave impressionist Frank Calliendo a career, or as a guest voice on The Simpsons.

Madden was, like Howard Cosell before him, one of those sports broadcasters who crossed over as a pop culture superstar. He was a superb coach, amassing a 103-32-7 won-loss-tie regular season record over ten seasons coaching the Oakland Raiders — the second-highest winning percentage in NFL history.

As a TV analyst, he became widely admired for being able to get into an athlete or a coach’s head, instantly break down a play and explain it in terms that even casual NFL fans could follow. Tony Romo gets a lot of credit for doing that today, but Madden was funnier and more entertaining. He parlayed that ability into big money, signing a four-year, US$32 million contract with Fox prior to the 1994 season. That was a better deal than any NFL player at the time.

He eventually called games for all four major networks, starting with CBS in 1981 where he was most effective opposite veteran play-by-play man Pat Summerall.

advertisement

Madden’s career was winding down in 2008 when I was on of many reporters attending an NBC Sports session at a winter meeting of the Television Critics Association in Los Angeles.

At that point, Madden, paired with Al Michaels, was helping to establish Sunday Night Football as one of TV’s most-watched attractions. At the packed TCA conference, he got more questions about his fear of flying and traveling to games on his custom-made bus than anything to do with football. Part of his act was awarding turkey legs or other food items instead of game balls at the end of broadcasts.

Terms such as “All-Madden” or the “Madden Curse” (players appearing on later versions of the Video Game box often slumped that season) were by then part of the football vernacular. In the booth, there was no game too dull Madden couldn’t liven up with a few well-placed doodles on a telestrator.

Give Madden credit, therefore, for knowing when to quit. He was 73 when he bowed out after the 2009 Super Bowl. He was never hurting for money; his endorsement of the NFL video games has spanned almost three decades.

One last note: Madden himself confirmed he turned down the part of Coach Ernie Pantusso on Cheers, a role that went to the late Nicholas Colasanto when the series began in 1982. While it’s easy to see him ace that role, credit Madden also for knowing what TV jobs not to take.