Martin Luther King Day in America seems like an apt time to review “One Night in Miami.”

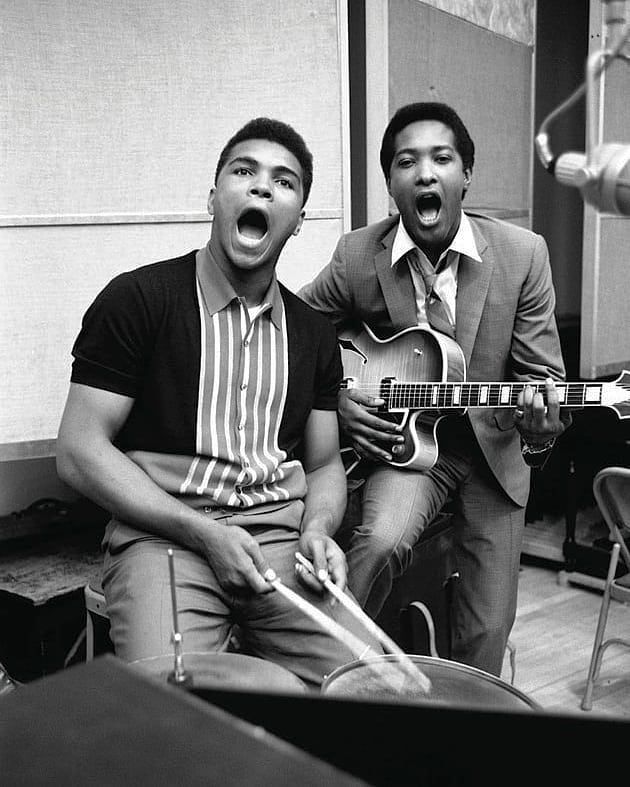

Based on a play by Kemp Powers (who also wrote this screenplay), the Amazon Prime Video feature fictionalizes an actual meeting between icons Malcolm X, Muhammad Ali, Jim Brown and Sam Cook. The four gathered in a simple room at the Hampton House hotel in February of 1964, hours after Ali shook up the whole world by defeating Sonny Liston to become heavyweight champion.

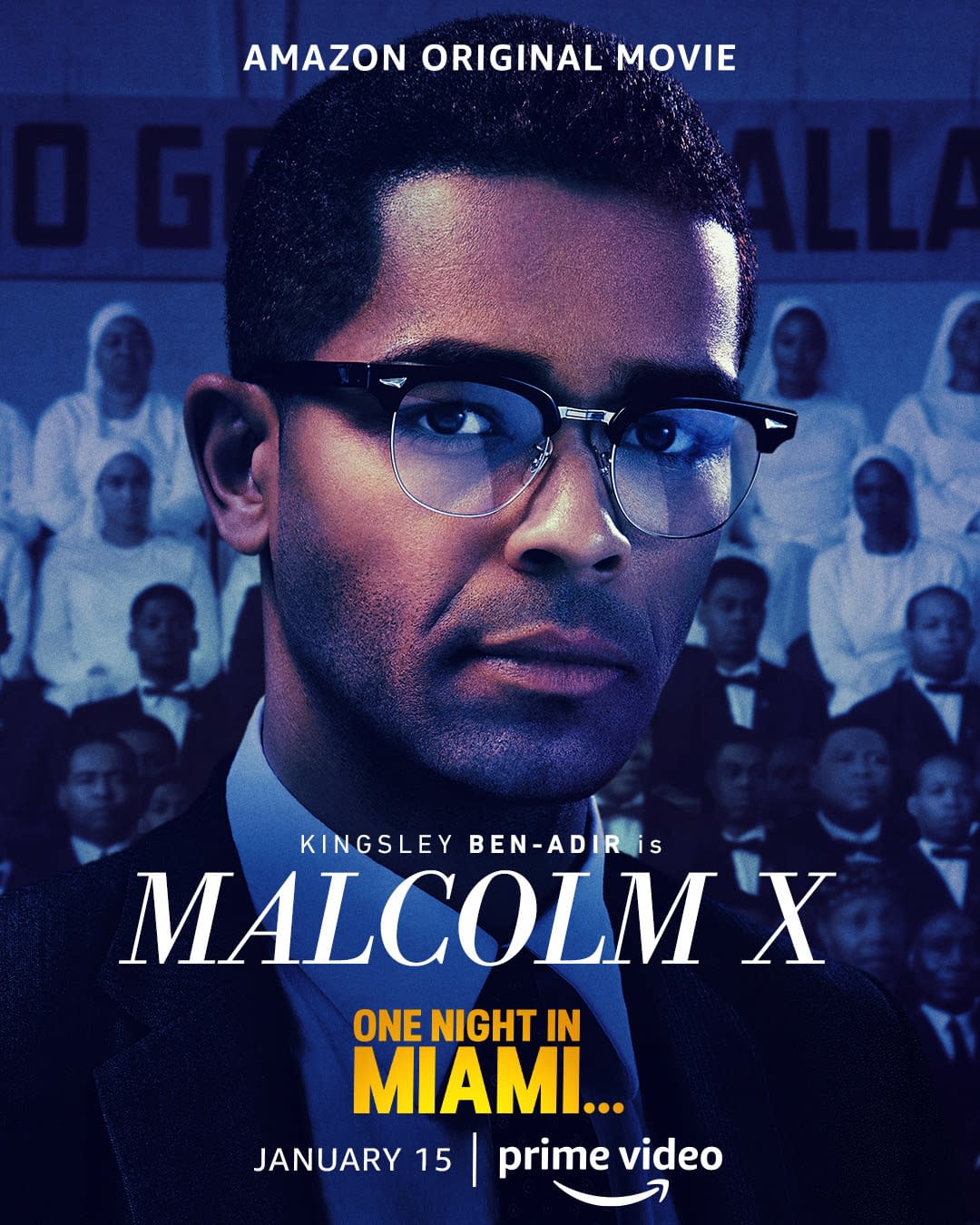

Kingsley Ben-Adir, Eli Goree, Aldis Hodge and Leslie Odom Jr. play the four superstars. Oscar- and Emmy-winning actress Regina King directs.

Works of fiction based on real life people and events are a hot ticket right now. They stir interest in everything from The Crown to Murdoch Mysteries.

It’s fun to imagine what was said at a critical juncture when historic people meet. There have been movies made about when Elvis met Nixon, or even Nixon met David Frost, that were intriguing and effective.

Such depictions, however, inevitably lead to squabbling. I loved it when a hermit painter named John Lennon steals four minutes of the film “Yesterday,” for example, although that was pure wish fulfillment. I laughed when the Beatles’ tradmark Italian boots were all you saw from under a bed in the Plaza hotel in 1978’s “I Wanna Hold Your Hand.”

advertisement

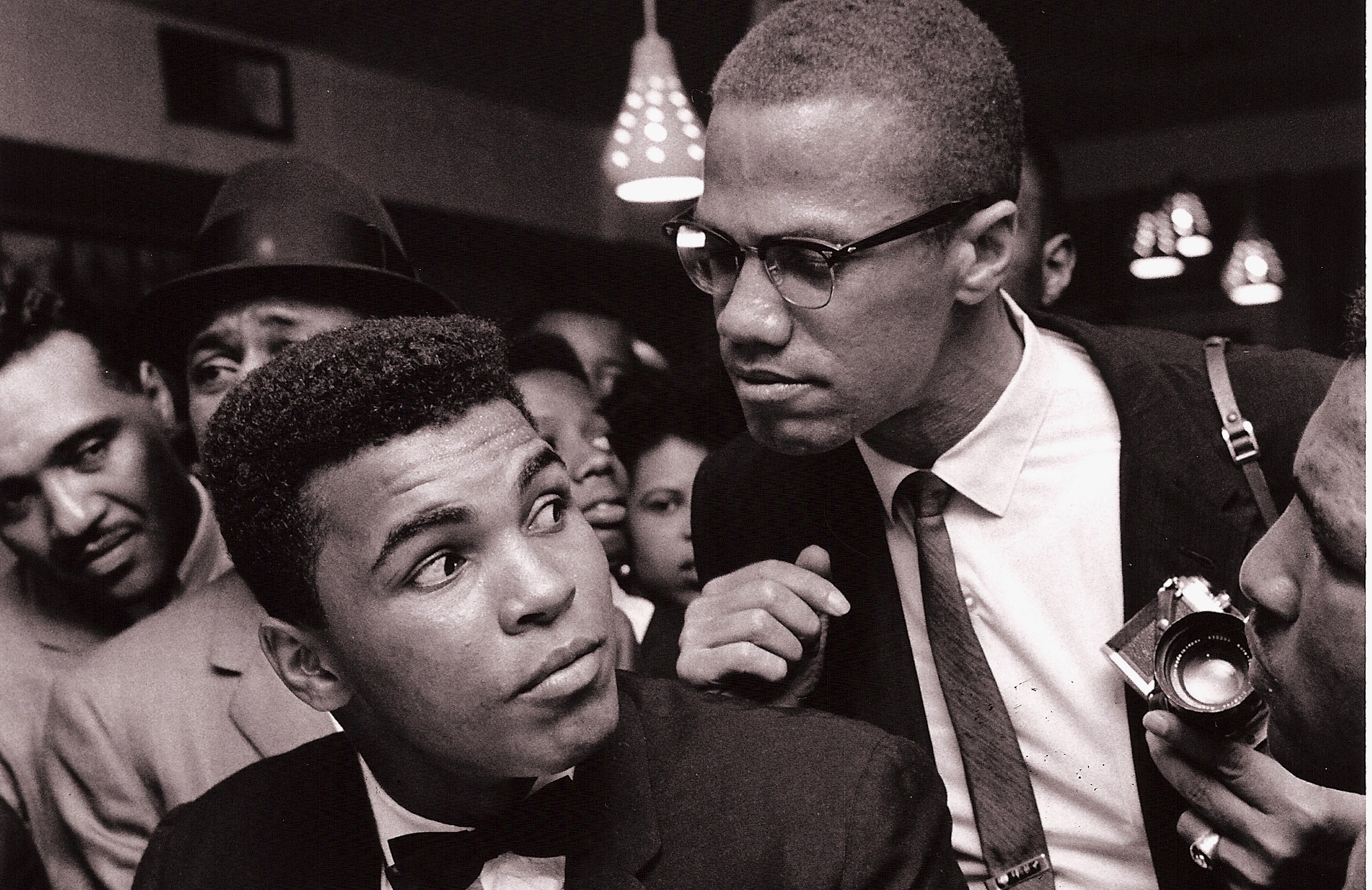

The Beatles clowned with Ali at his training camp in Miami a week before the Liston fight and the events of this movie. They also visited Elvis at Graceland, a meeting that was never recorded and calls out for a Crown-ing. So does Ali’s actual odd couple pairing with boxing nemesis Joe Frazier on a long car trip to promote their first fight.

What is most intriguing about the Malcolm X-Ali-Brown-Cook summit is the timing. Not only is Ali the newly-minted champ, he’s also, through his friendship with X, about to become a highly controversial member of the Nation of Islam. A black Muslim was even more frightening to many white North Americans in 1964 than a black heavyweight champion. A fuse was about to be lit that would explode then, and in many ways continued to explode, this past January 6th.

“One Night in Miami” sets things up by going back to when Ali — then named Cassius Clay — fought British champion Henry Cooper in June of ’63. The 21-year-old Ali stopped Cooper in the fifth round, but the fight was notable as the first time Ali was ever knocked down.

In the film he’s stretched out and dazed as the referee goes into his count. In real life, Ali popped up again so fast it was as if he was on a string.

This will sound picky, but this early bit of artistic licence to make a point made me start to question the veracity of much of what followed.

Remarkably real, however, is Goree’s performace as Ali. This is a thankless role because Ali was such a towering, one-of-a-kind figure he’s almost impossible to duplicate. It’s like, to reference a song by The Odds on actors who play Jesus — no one ever comes close. Will Smith as Ali? Forget it.

Goree, a Canadian Film Centre grad from Halifax, has the benefit of being relatively unknown (certainly compared to Smith) despite credits on Ballers and dating back in Canada to Motive and Flashpoint. He’s also exactly the right height as Ali and he clearly went to school on the champ’s posture, histrionics and cadence, especially in the quieter, private moments.

All four of the leads, for that matter, admirally inhabit their characters. British actor Ben-Adir has the trickiest job depicting X, who already had a giant target on his back from within and without his community. The actor finds the balance of fear and conviction that had to be consuming the real man in February of ’64. He also looks remarkably like his character.

Hodge steps into Brown — the only one of the four still alive — with power. He has a very effective scene, early on, opposite Beau Bridges at a stately plantation house. It’s a moment that sets the racial divide sharply in the context of the times.

Odom, Jr., is less defined for me, but then so is Sam Cook. The pop/soul singer was dead by December of that same year, shot to death in a motel at age 33. Two months later, X was also gunned down.

King shows promise as a director, at one point capturing all four bolting out of a Lincoln convertible with its showy, suicide doors. The overhead shot is a stylistic highpoint.

It’s when we get to the hotel room that “One Night in Miami” seems to stall. Malcolm X has brought them there with the promise of a party. That the three others stick around for what is essentially a soul-searching, religious and cultural awakening — seems a bit far-fetched on the night of Ali’s historic athletic triumph.

I get that it makes for an interesting premise, but it seems all four would have to be trapped in an elevator for things to have extended past ten or 15 minutes. I’m guessing, as well, that this worked better on stage in a theatre setting.

For me, as a film, the lengthy motel scenes provide insight and history, but do not seem to build as drama. There are moments. It’s cool to see X, for example, confront Sam Cook with some era-defining Bob Dylan music on a turntable. That leads to a flashback to when Cook handles a power shortage at a live performance by leading an audience into a spontanious and rousing rendition of “Chain Gang.”

In the wake of a searing summer filled with racial strife and Black Lives Matter rallies across North America, “One Night in Miami” is certainly timely and welcome. It is also one reason why it arrives with high expectations. That it takes four such dynamic, historical leaders and puts them together in one room should have led to more fireworks. There is still plenty to ponder and admire, however, especially for viewers born long after these guys rocked the world.

A first step, if I can make one suggestion: follow this link to the time Malcolm X crossed the border into Canada to make an appearance on the panel show Front Page Challenge. It’s an extraordinary culture clash that says a great deal on how much the world has changed in 57 years. The old white men panelists — hardened media men such as Gordon Sinclair, Pierre Berton and Charles Templeton — respectfully ask intelligent questions and get strong, reasonable responses. There’s a civility and an exchange that just doesn’t seem possible now.

The show, and the world, were more black and white back then. And so it goes.