While it was a time of bewilderment and sorrow, it was also a privilege to be in a newsroom on Sept. 11, 2001. At the Toronto Sun, where I was working in those days, it was battle stations, all hands on deck. The newspaper put out a “bugle” edition that day (a special, afternoon edition), the first time in 25 years, if memory serves, the paper had hit the streets with anything other than a morning run.

Being the TV critic, I’d usually be getting out of the way in the midst of what was and still is the hard news story of the century. The entertainment section wasn’t called “the toy department” for nothing. But right from the beginning, television was the rest of the world’s window on the tragic events unfolding in New York, Washington and elsewhere. The horrifying images of the World Trade Center in flames was on every channel. (Even though there was no Twitter or Facebook, everybody got the message to watch.) So I was asked to chime in, and to cover what was happening on-screen I had to fight my way in front of the one or two TV sets in the newsroom along with everybody else.

The demands were instantaneous as well for the electronic press. Speaking with Lloyd Robertson recently, he recalled being woken up on the morning of 9/11 and told to get straight to the CTV newsroom. When he arrived he stayed on the air for 14 hours straight. Peter Mansbridge and Kevin Newman, then just days into his job as anchor of Global National, served similar iron man stints.

The guy I remember being so impressed with was another Canadian, ABC’s Peter Jennings. Besides his usual authoritative calmness, he just seemed so on his game, stopping to ask firefighters and emergency workers what he was not getting from the unfolding story. Jennings raised the level of coverage, never stooping to showboating, always focused on being a reporter.

Back then, besides my daily TV column, I was doing a series of weekly entertainment-based editorial cartoons at the Sun and the two drawings used here appeared around that time. I was trying to scratch an old artist itch, although I found after half a year that writing and drawing, often at the same desk day of deadline, did not mix. But it was cathartic to me at least to try and work out the madness of 9/11 in a visual way.

The first drawing, above, appeared the following Sunday and was my attempt to show how TV was everybody’s way into and of coping with the tragedy. The second drawing, at the top of this post, comes closer to what I had to cover in those days. The world was a fragile place in the days following the terrorist attacks.

The Fall 2001 TV season was just about to start and the networks were struggling and scrambling in response to the attacks. Fox had this brand new show 24 and the pilot featured a terrorist blowing up a commercial jet. Jack Bauer looked like he was going to get yanked off the air before his first bad day had even begun. Another CIA-themes adventure series, The Agency, was benched and quietly slipped off the radar. The WB had to postpone its lighter-than-air Friday premieres twice.

In Canada, 50 new digital specialty channels had launched just days before. If anybody needed Lonestar or Drive-In or the women’s sports channel before 9/11, they didn’t afterwards. Those digital channels never became the next great profit centre many in the industry had envisioned.

Award shows were canceled, postponed or, in some cases, muted. Gone was any red carpet frivolity. Ellen DeGeneres earned respect for soldiering on as host of a very toned down Emmy Awards. Several silly reality shows were derailed or canceled. Everything got very sombre and serious.

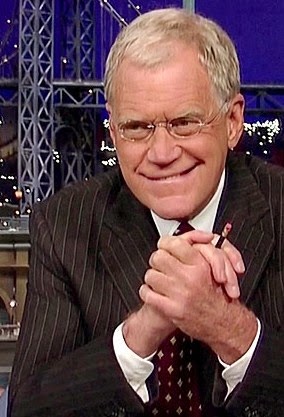

The guy who showed it was all right to go back on the air was David Letterman. In what may have been his greatest moment, Letterman opened his nightly talk show without the usual theme or visuals and went straight to the desk, delivering a heartfelt soliloquy about the “terrible sadness” in New York one week after the attacks. For 20 years an icon of irony and sarcasm, Letterman set a new tone of grace, dignity and courage.

This was, of course, six or seven years before the “Late Night Wars” when everything slipped into a nasty mud fight.

Shortly after Letterman’s return, tens of millions of dollars were raised for victims of 9/11 and their families in a live, candle-lit, star-studded musical special America: A Tribute to Heroes. It was a brief, shinning moment of calmness and sanity, a movement away from the vulgarity of celebrity and toward the celebration of real individuals.

Then it all stopped. By the new year, it was The Osbournes, The Bachelor, Celebrity Boxing and Anna Nicole Smith. The distractions were back, and they were dumber than ever.

TV has been dumbed down in reaction to a crisis before. In the months following the assassination of president John F. Kennedy, North American audiences embraced The Beverly Hillbillies. Some of those episodes from January, 1964, still rank among the highest-rated TV episodes of all time. By the time February rolled around and The Beatles hit Ed Sullivan, TV audiences were ready to hold anybody’s hand.

The war in Vietnam had been picked at like a scab by the Smothers Brothers on their controversial CBS variety show. Tired of censorship battles and wary of the new Nixon administration, CBS silenced them in April of 1969, replacing The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour with Hee Haw.

Bill Maher often jokes that he’s the only TV star who got fired over 9/11. After he raised eyebrows by pointing fingers at the terrorism response on his ABC series Politically Incorrect, he was pretty much phased out of the timeslot. His replacement the next January? Man Show joker Jimmy Kimmel (who evolved into a brutally honest late night voice; look for him in Toronto this week working TIFF). Political jokster Dennis Miller was also out at HBO in the months following 9/11.

Then again, in the decade since the terrorist attacks, Jon Stewart’s Daily Show has emerged as the place where every politicians feet are held over fire. Bill Maher’s New Rules–a far more biting and outspoken showcase than Politically Correct–had been extended into a ninth and 10th season. Letterman spent eight years relentlessly hammering away at the Bush administration.

All in the Family did premiere less than a year after the Smothers were silenced. Television is a house of many windows and not all the open ones were shut after 9/11.

1 Comment

You’re forgetting about Howard Stern, the only on-air comedian who didn’t take a holiday the week of the tragedy. The attacks happened right in the middle of a story he was telling about Pam Anderson. But once they were aware of what was going on, the tone of that particular show dramatically changed. Stern ended up staying on the air two or three hours longer than usual. That week and, I believe, beyond, he allowed affected merchants to call in, plug their business and ask New Yorkers to support them. He probably regrets some of the comments he made that day (and for the next three years as he foolishly supported the second Iraq War until finally coming to his senses) but having heard the replay of that part of the show a year later, it was one of his best broadcasts, even though it would’ve been nice if he mentioned that imperial America’s involvement in the Middle East just might have played a role in the murders. While all the late night comedians hid from their studios for a week, Stern and his loyal crew never took a break. He deserves all the credit in the world for that but he’ll never receive it.

Also, you forgot to mention The Concert For New York City that Paul McCartney organized where Stern made a typically funny guest appearance. Terrific benefit with lots of strong performances and an immediate public forum for those to vent their anger and dispair at the radicals who coldly attacked their friends, co-workers and families.