In the past few weeks, I’ve posted a couple of “From the Vault” episodes over at brioux.tv: the podcast. One featured a 2014 interview with Bill Daily talking about his boss on The Bob Newhart Show; the other was another 2014 interview, this time with WKRP in Cincinnati creator Hugh Wilson.

I’ve done others in the past, digging through old cassette tapes for conversations from my earliest days at TV Guide Canada. These were with George Burns, Jack Paar and Michael Landon.

Re-purposing past conversations and sharing them years later as podcasts or in documentaries such as the new HBO original Elizabeth Taylor: The Lost Tapes, is a bit risky. On one hand, thoughts shared one-on-one can be less guarded, more intimate. The Taylor doc is based on 40 hours of recorded conversations, conducted in 1964, with Richard Meryman. Taylor was talking to a trusted journalist one-on-one, with no concept that this might someday be shared with a click on something called Max.

There is a responsibility however, I believe, to be somewhat judicial when editing. Basically, are there parts of the conversation that put the subject in a bad light? In particular, can thoughts shared from the ’60s, ’80s, or even earlier this century betray views that may have seemed acceptable then, but, in these “woke” times, seem insensitive or even downright offensive today?

It is a line I’ve had to walk a time or two. You don’t want to be responsible for casting somebody in a light that they are no longer around to defend or even address. As a result, I do not share everything I pull out of the vault.

On the other hand, there is some fascination in providing a window on how things were expressed and discussed in earlier times. If I had taped a conversation with Judas Iscariot, for example, I’d be tempted to share it in a podcast on the subject of the last supper.

advertisement

All of this comes down to a simple truth: everybody loves a good story. Few of us, likewise, are above a little eavesdropping. In the right hands, a documentary based on past taped conversations can be very compelling and revealing, as it is in Elizabeth Taylor: The Lost Tapes, now streaming on HBO/Max and Crave.

Meryman died in 2015. Recently, his archive of recorded conversations were discovered. The responsibility fell to director Nanette Burstein to do the editing and still let Taylor’s own voice be the backbone of this new documentary.

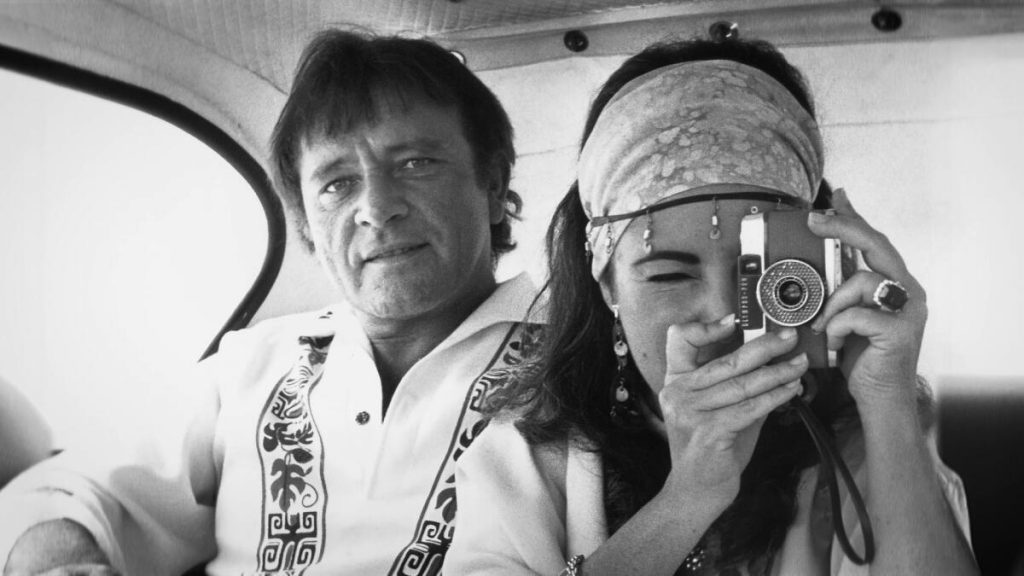

What is mainly revealed in Burstein’s film is how our seemingly instatiable obsession with celebrity was just as big a tabloid tsunami 60 years ago as it is today. There was no social media when Taylor and Richard Burton were caught up in an adulterous, combustable love triangle with Eddie Fisher. There wasn’t even Entertainment Tonight. Yet my mom and my aunt had all the dirt back in the day without ever leaving their suburban corners of Toronto. The news was in every grocery store, some of it racked right by the cash register but also in the neighbourhood newspaper box.

In the documentary, it is shown visually in headlines and in well curated film footage. That includes shots from 1964 of newlyweds Taylor and Burton making the scene in Toronto where Burton was appearing in “Camelot.” This followed a well-publicized romance ignited on the set of their big budget costume drama, “Cleopatra.”

It is Taylor’s own voice that adds an extra layer of poignancy and interest to this compelling documentary. Meryman, who was working on a book, pulled plenty of insight and original thought out of Taylor. You can hear, first-hand, her exasperation, her frustration, and especially her wit, some of it self-effacing.

Even Taylor calls out her marriage addiction. “I’ve been married too many times,” she tells Meryman. She wed seven men in her eight weddings, with Burton taking her hand twice. Other archived voices in the documentary include Burton, Taylor’s lifelong friend Roddy McDowell, Fisher’s ex- Debbie Reynolds and George Hamilton. Equally fascinating are scenes and comments from Mike Todd, Taylor’s big-spending producer husband who died in a plane crash, ending the match that might have stuck.

It is Taylor, however, who knew her own predicament best. Starting out as a child star, she had plenty of perspective. “I don’t like belonging to the public,” she says, “and if you try to explain, you lose yourself along the way.”

That she and Burton chose to get all aged up to play a feuding, fifty-something couple of alchoholics in 1966’s “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” seems almost heroic. These two were a lot of things, but it is heartening to be reminded that they weren’t just tabloid fodder; they were also artists.