I’ve always been a big fan of Albert and David Maysles. The “direct cinema” documentatians went on to make Gimmie Shelter (1970) and Grey Gardens (1975). Before those films, the brothers captured lightning in a bottle with their black and white record of The Beatles first visit to America in February of 1964.

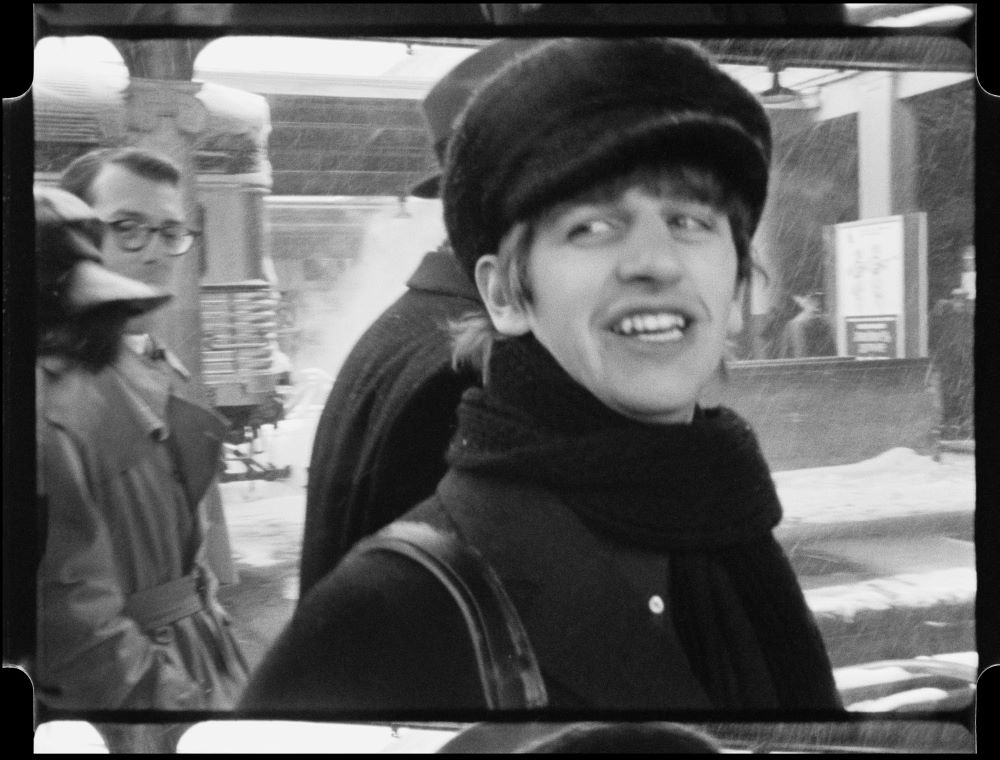

Unlike The Beatles ubiquitous music, it is hard to put the Maysles’ achievements in context. Albert, the cameraman, and David, who recorded the sound, should not have been able to get what they got with the available equipment they had. Their swiftness and portability was incredible for the times. These guys had to get up close and personal, capture moments on film before and after changing reels, with machines not yet designed to run and gun they way they did. Today you can do it all with a smartphone. Back then, it was heavy, analog and where the heck was the lighting guy??

Albert, in fact, MacGyvered his camera, ditched his a tripod and constructed a brace to help hold his shots steady. David recorded on a Nagra, a separate reel-to-reel machine. The brothers figured out their own low tech way to keep sound and pictures in synch. You can see The Beatles tapping in, slating the sound and picture, throughout their documentary.

And they did it with about an hour’s notice to from the record company to get to JFK airport and shoot this new group from Liverpool who were arriving in America.

The new AppleTV+ documentary Beatles ’64 is not about the Maysles but it would be about 20 minutes long without their amazing footage. McCartney later worked with Albert again on The Love We Make (2011), a documentary on the ex-Beatles’ experience in New York in the days following the 9/11 attacks. Interviewed at the time of that doc, McCartney told a Television Critics Association gathering in 2011 that Maysles was a guy with a twinkle in his eye.

“Anyone who’s a great artist with that twinkle is special,” McCartney told us, “because you can get on very easily with him.”

advertisement

The artists making Beatles ’64 twinkle as well I’m sure. Executive producer Martin Scorsese, who previously produced and directed George Harrison: Living in the Material World (2011), certainly twinkles. David Tedeschi, who edited the Harrison doc, remains tight with that Beatles’ widow, Olivia. She is listed among the new executive producers, as are surviving Fab’s Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr. Sean Ono Lennon is also credited. Gilles Martin, son of The Beatles legendary producer George Martin, remixed (using technology developed by Peter Jackson while making Get Back) “She Loves You” and other music used in the film.

It all comes together with a little help from these friends. If you are a Beatles nut however, old enough to have seen the “mop tops” on Ed Sullivan (and you can remember your parents’ reaction), you truly have seen it all before.

Even if you are not that old, good luck avoiding The Beatles in the streaming era. Right now you can see Jackson’s gloriously restored, eight hour epic Get Back from 2022 as well as a cleaned up version of the 1970 documentary Let It Be on AppleTV+. Ron Howard’s documentary of the groups live tours, The Beatles: Eight Days a Week, came out restored (and in some concert scenes, colourized) in 2016. Even the Maysles original doc, released in 1964, resurfaced on DVD in 1991 as The Beatles: The First U.S. Visit.

Celebrating the 60th anniversary of the group initial New York triumph, Beatles ’64 seems more made for the generations that never even heard about The Ed Sullivan Show. Two Beatles (John Lennon and George Harrison), George Martin, even roadie friends Mal Evans and Neil Aspinal, are long gone.

On the 40th anniversary, in February of 2004, I happened to be in Manhattan. The Ed Sullivan Theatre fitted a fake canopy over the actual David Letterman marquee with the original playbill out front. It named other performers that Sunday, including Tessie O’Shea and the Broadway cast of “Oliver!” featuring a future Monkee, Davy Jones. I stopped by The Plaza Hotel where The Beatles stayed and asked if any of the staff present four decades earlier still worked there. One fellow was summoned and gave me his story outside on the same steps where hundreds of screaming fans once stood.

The Beatles ’64 filmmakers found a handful of people who saw the group that winter in America or were electrified by the Sullivan Show performance. Among them is Smokey Robinson, whose song, while with The Miracles, “You’ve Really Got a Hold On Me,” is among The Beatles’ best early covers. There is a soulful, ’60s performance by Robinson of “Yesterday” that is one of the less played-out nuggets found in Beatles ’64.

Robinson makes the point that The Beatles were the first big white music group he ever heard who always credited black American music as their inspiration. Writer and critic Joe Queenan talks about how his dad so despised the group that he would not allow his children to watch the Sullivan show that night. Thankfully, a nearby uncle came to the rescue and invited the kids over.

There is a whole surprising side story in Beatles ’64 about a young American musician so inspired by the group’s early recordings that he and a friend sailed off to the group’s home base in Liverpool, England. With no documents upon entry, the two young Americans were held for six days and about to be booted back home when their story appeared in a local newspaper. That tale comes full circle late in Beatles 64 and the pay off is a doozy. The doc also begins with a rapid cold opener of U.S. president John F. Kennedy’s rising promise and tragic end, setting the table for America’s embrace of anything that could lift its spirts.

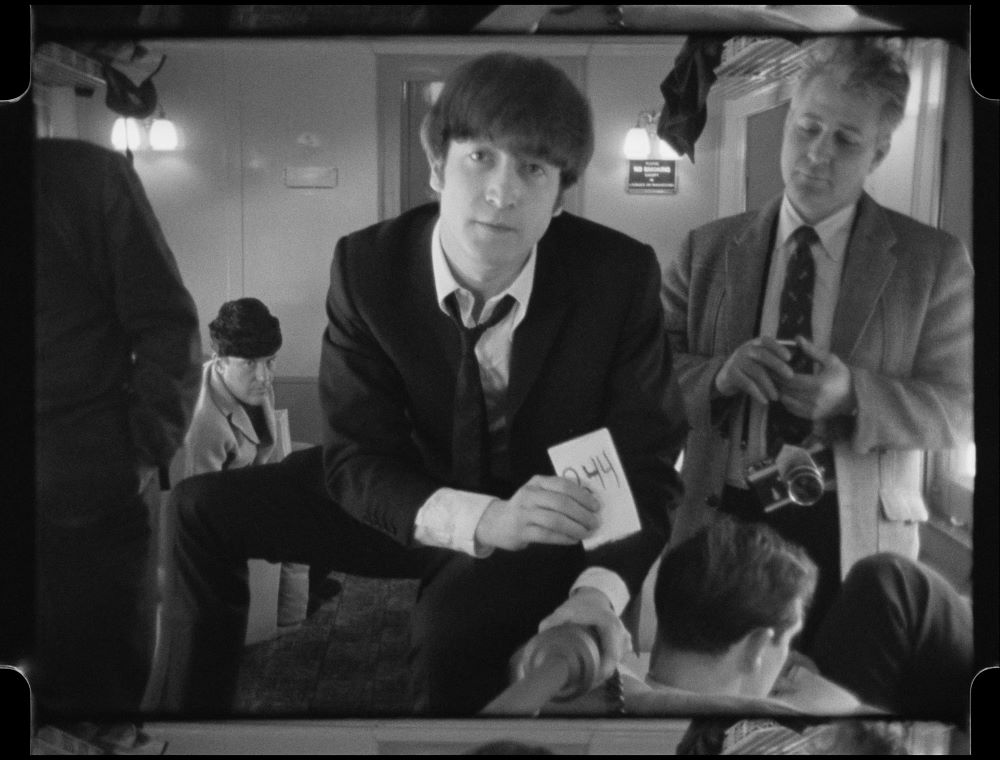

Those are all good reasons to watch Beatles ’64. Left out was the story of how the Maysles, who were non union, were not allowed to shoot backstage footage of the Ed Sullivan appearance. (They scrambled and knocked on nearby doors, finding a family with young girls watching the show and filmed that instead.) Or why there were only three Beatles in Central Park for that photo shoot. (George was sick.). Or who was that blonde glimpsed with Lennon on that trip. (His wife Cynthia. As the title that was super-imposed over Lennon on the CBS broadcast read, “Sorry girls he’s married.”)

None of that matters. As the great PBS documentarian Ken Burns once told me when I quibbled about his film on Muhammad Ali, “Change it then when you make your own documentary.”

Still, it seemed as if there could have been other voices added. One of the best talking heads in the recent Netflix documentary “Return of the King: The Fall and Rise of Elvis Presley” is Conan O’Brien. He just has a way of conveying the immediacy of what he saw on TV in ’68 and putting it in context. O’Brien was three when The Beatles played Ed Sullivan, but there had to have been somebody else — Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen (also very effective in the Elvis doc) or, who knows, David Letterman or Paul Shaffer. Both worked for years in the same Sullivan theatre in Manhattan when everything changed in ’64.

An archived interview with Ronnie Spector, who died in 2022, is effective, especially the part where she talks about helping to sneak the Fabs uptown into Harlem in the midst of that first visit craziness. It was also great to hear from Harry Benson, now 94, the Scottish photographer who covered that first American trip in ’64.

It was a reasonable idea to capture new footage of McCartney commenting on an exhibition of his own photographs from 1963 and ’64 at the Brooklyn gallery. He and Ringo, however, tend to fall back on the same stories. (McCartney: “Me dad said, ‘D’ya hafta sing, ‘Yeah yeah yeah’? Can’t it be, ‘Yes, yes yes?'”)

No Peter Jackson or A.I. machine, of course, can ever truly give us the perspective of John or George today. Their archived clips are well chosen, however, including one where Lennon observes that the end of conscription in England — a few years before he and his mates might otherwise have been drafted — allowed The Beatles and their contemporaries to become this new army of musicians and artists.

Beatles ’64 does also give Lennon the last word, and it is wry and apt and matter of fact. He puts it all in simple perspective. Beatles ’64 will as well, although more for the many who have not gone down this long and winding road than those born before Yesterday.