In the summer of 2010, Nichelle Nichols was one of the featured guests at a session of the Television Critics Association press tour. She was there as one of the “Pioneers of Television,” a PBS series that saluted older stars.

Nichols, who passed away July 30 at 89, was joined at the session by Martin Landau (Mission: Impossible), Mike Connors (Mannix), Robert Conrad (The Wild, Wild West) and Linda Evans (Dynasty). A dozen years later, only Evans remains.

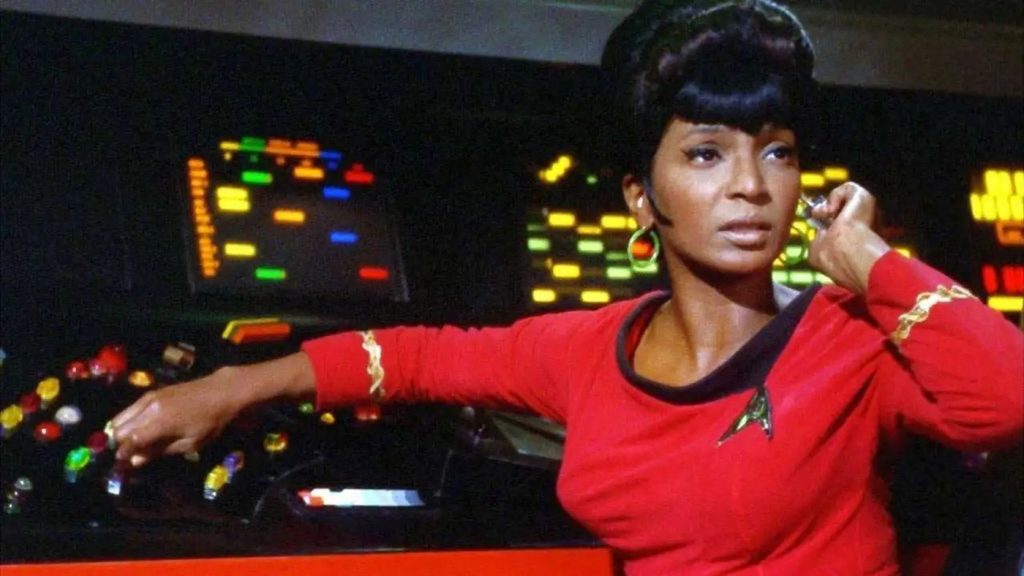

Nichols looked regal in her white hair and colourful wrap and jewelry. She was, of course, best known as Lt. Uhura, fourth in command on the original Star Trek (1966-69). We were reminded that she started out as a singer who toured with Lionel Hampton and Duke Ellington. Her aspirations were on Broadway, but she took TV roles to help raise her profile. In one, she landed an episode on a series created by producer Gene Roddenberry called The Lieutenant. That series went nowhere, but the two were briefly an item, and Roddenberry remembered her when it came time to cast Star Trek.

“I took Star Trek,” she told reporters, “because I thought it would be nice adjunct to my resume, and I’d get to Broadway quicker and as a star.” Basically, added Nichols, “Star Trek interrupted my career.”

Nichols has told this story many times over the years, but it is a good one. She tried to leave Star Trek after the first season because, she thought, “this is going nowhere for me.”

She told Roddenberry she wanted off the show. He told her he really wanted her to stay and asked her to think about it over the weekend.

advertisement

The next night, Nichols attended an NAACP fundraiser. She was approached by one of the organizers who wanted to introduce her to a big fan: Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

King told her that Star Trek was the only show that he and his wife (Coretta Scott King) allowed their three children to stay up late to watch.

The meeting had great meaning for Nichols. On newscasts in 1967, in the thick of the Civil Rights movement, “you could see people who looked like me being hosed down with a fire hose and dogs jumping on them because they wanted to eat in a restaurant.

“Here I was,” she told critics, “playing an astronaut in the 23rd century.”

Nichols told King that she was leaving the series. “You can’t,” he replied.

King understood that what Roddenberry established was the notion that, in the 23rd century, a Black woman could be a commander on a space force.

What King told her, she said, was that she was “part of history, and this is your responsibility even though it might not have been your career choice.”

The next day, Nichol told Roddenberry about her encounter with King.

“And Gene Roddenberry was a 6-foot-3 guy with muscles. He was a big, hack-nosed guy. He had been a motorcycle cop and flying hero in the second world war. And he sat there with tears in his eyes. He said, ‘Thank God that someone knows what I’m trying to do. Thank God for Dr. Martin Luther King.’”

Nichols said that if Roddenberry would still have her, she’d stay on the series. “And he took out my resignation and had — and it was all torn up where I had given it to him. And I stayed and I’ve never looked back.”

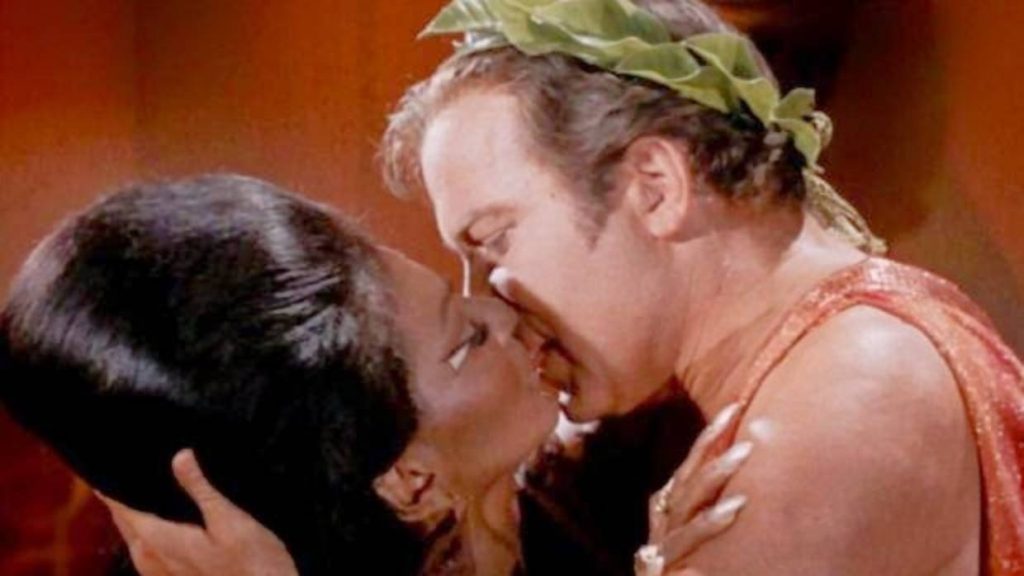

The other often-told story involving Nichols and Star Trek is that her character and Captain James T. Kirk (William Shatner) shared broadcast network television’s first interracial kiss.

Not true. About a year before the episode, “Plato’s Stepchildren,” aired in November of 1968, Sammy Davis Jr., and Nancy Sinatra shared a kiss on the 1967 variety special “Movin’ with Nancy.”

The Star Trek episode itself is inconclusive. The somewhat kinky storyline had these leaders on another planet trying to make Kirk and Uhura kiss using mind control. If you watch the episode closely, it doesn’t look like their lips actually touch. Shatner turns his face at the last moment. We find out that Kirk and Spock (Leonard Nimoy) got their hands on a mind control antidote at the last minute. What you have, therefore, is TV’s first inter-racial air kiss, the Platonian pseudo pucker.

Why all the fuss? in 1968, months after the assassination of Martin Luther King, NBC feared affiliate stations in the South would not show the episode. In her 1994 autobiography, “Beyond Uhura: Star Trek and Other Memories,” Nichols notes that the network did get mail from Southern viewers, and that the response was more positive — although perhaps just as unenlightened — than the network feared.

“I am totally opposed to the mixing of the races,” one White Southerner wrote Nichols. “However, any time a red-blooded American boy like Captain Kirk gets a beautiful dame on his arms that looks like Uhura, he ain’t gonna fight it.”

Shatner’s memory, often a tad suspect, is that two versions were shot — one kissing, one missing. The second shot made the cut and is the only one shown in reruns.

In August of 2006, Nichols was a guest on the raunchy Comedy Central roast of William Shatner. Nichol looked at her former co-star — who apparently wasn’t too popular on the Star Trek set — and said, “Let’s make history again — and you can kiss my black ass!”