Last year, when I was at the south end of Vietnam in the Mekong Delta (tracking contestants of The Amazing Race Canada), the sound of passing riverboats had a strange but familiar ring. Far enough in from the shore so that the source of the sound could not be seen, the tiny outboard engines with their long propeller shafts sounded like the overhead whir of helicopter blades.

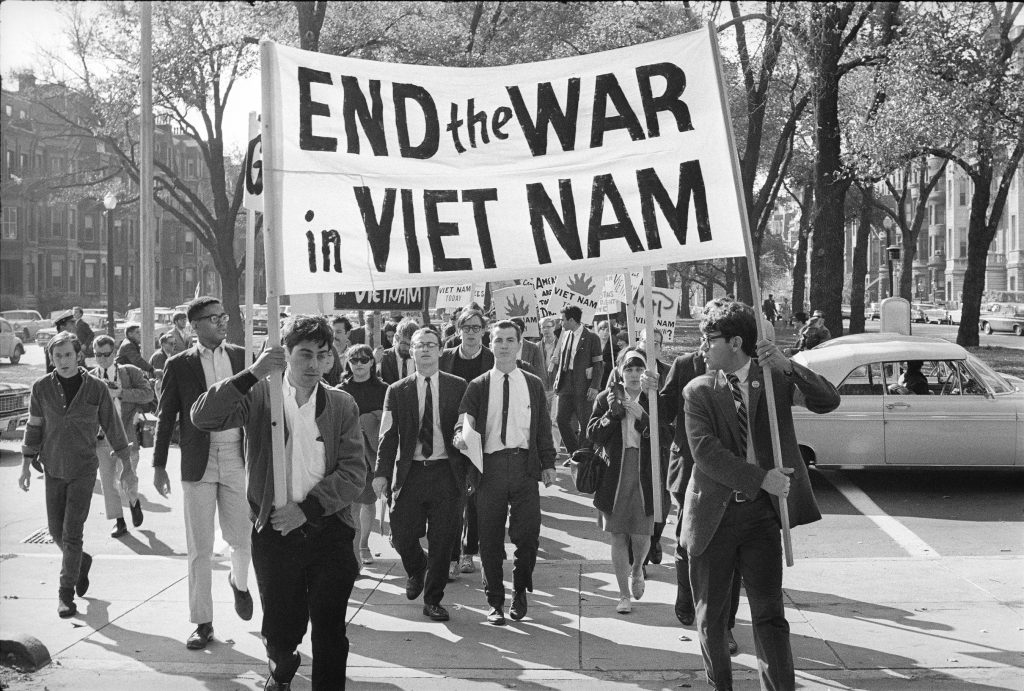

It was a steady “fhut-fhut-fhut” sound I almost expected to hear in this region. That’s because I was raised in the ’60s, back when the war in Vietnam was updated nightly on the evening news — and choppers were a constant part of the TV news soundtrack.

The same association is made at the start of The Vietnam War. The 10-part, 18-hour documentary series, from award-winning filmmakers Ken Burns and Lynn Novak, premieres Sunday night at 9 p.m. on PBS. The steady beat of chopper blades is the first sound you hear as each episode fades up from black.

Growing up in Toronto, I was a great lake removed from the U.S. draft. Yet I remember waking up in a night sweat, terrified I might someday get my letter from Uncle Sam and have to go and fight in Vietnam. I remember the relief I felt swiftly realizing Canada did not draft soldiers to fight in that war. I was probably 10 years old, but years of following the “Living Room War,” especially on Buffalo, N.Y. network affiliate stations, had me rattled. Most Canadian kids in 1967 were thinking more of Expo ’67, or Batman, or the Stanley Cup winning Toronto Maple Leafs than the DMZ.

Burns and Novak have spent over 10 years crafting this touchiest of all TV time capsules, which lands at a deeply divisive point in American history. They purposefully set out to tell both sides of this very long war, interviewing many soldiers, civilians and others affected on the ground.

Burns’ usual documentary subjects, including the Civil War, jazz, baseball and the Roosevelts, date back before or more towards the early part of the 20th century. There are fewer eye witnesses, although some were used — just in time and to great effect — in his documentary on World War II.

advertisement

With fewer contributions from historians and other experts, Burns and Novak allow those who were there, from both sides do the talking.

There is also a tremendous wealth of archival new footage, bringing viewers right into the war some of it very hard to watch. All war is different parts valor and honor and atrocities but no wars up to that time every had all three documented to such an extent.

Many still photos — some shot by photo journalists who gave their lives to cover the war — also help tell the story. I visited the War Remnants Museum in Ho Chi Minh City (formerly Saigon) last year and the photo exhibits were among the most moving aspects of the collection.

The documentary covers the usual territory, examining the roles played by American presidents Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon as well as Henry Kissinger, their chiefs of staff and other political players. None emerge unscathed; leaders on the other side are shown warts and all, too.

Besides audio cues such as the chopper blades, the soundtrack is outstanding. For years, dramatic recreations of the war, be they China Beach or “Platoon” or “Apocalypse Now,” have paid hefty rights fees to The Rolling Stones, The Doors, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young and The Beatles and others to find the right emotional triggers. Nobody has ever approached the soundtrack put together for The Vietnam War. Besides the aforementioned there are contributions from Bob Dylan, Pete Seeger, The Byrds, Jimi Hendrix, Marvin Gaye, The Temptations and many more — 120 songs in all. That’s in addition to 90 minutes of new, original music from Academy Award-winning composers Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross.

Frequent Burns collaborator Peter Coyote narrates with an extra edge. I spoke with Coyote in Montreal at the start of the year on location with the upcoming CTV limited run series The Disappearance. He could hardly wait for The Vietnam War to air, calling it Burns masterpiece.

The question remains, however — will Americans watch? Many of the surviving servicemen and women still carry the scars — even those not wounded in combat. They never got the heroes welcome that their fathers got returning back from WWII.

As one ex-Marine says near the start of Sunday’s opener, the subject of Vietnam is like “living with an alcoholic father. ‘Shh — we don’t talk about that.'”

The one critic I most wanted to read on The Vietnam War was another ex-Marine: former Dallas Morning News journalist and blogger of distinction Ed Bark. Ed is a founding member of the Television Critics Association and is a TCA colleague from way back. He writes his informed and deeply invested impressions of the PBS documentary here. Other American critics I know either starved themselves in an attempt to avoid the draft or served in zones now considered so toxic at the time from deadly Agent Orange gas they are considered beyond lucky to be alive.

For them, and for all of us, this may be a hard documentary to watch. It is also the one show everyone — young and old, American, Vietnamese and Canadian — should watch this fall.