Norman Jewison turns 95 in July. His 24 feature films — 15 more than Quentin Tarantino — garnered 48 Academy Award nominations, winning two Best Picture Oscars (for “In the Heat of the Night” in 1967 and “Moonstruck” in 1987). The Thalberg Award winner helped create the Canadian Film Centre, nurturing and developing the next generation of Canadian film and television creators.

Surprising, then, that there really hasn’t been a scholarly biography written about the Toronto native until now. That has been addressed in an entertaining and compelling way in Ira Wells “Norman Jewison: A Director’s Life” (Sutherland House).

Wells spent three years working on the biography. A full year of that was pouring over Jewison’s papers, annotated scripts and other manuscripts at Victoria College at the University of Toronto — where Wells is an assistant professor of literature.

He writes that Jewison’s 24 feature films “could just as easily have been a dozen, or three or none.” Landing the next film deal, despite all the accolades, never got any easier. It helped that behind Jewison’s nice guy, all-Canadian persona, beats the heart of a lion. As Burt Reynolds once mused, “He must be able to kick the shit out of people in meetings.”

Jewison’s other talent was to be the director he needed to be in relation to the talent at hand. He could be, as Wells describes him, “a nurturing father figure, a wise older brother, on old fling.” Sometimes he was all three on the same film, as he was on the set of “Agnes of God.”

Wells goes through Jewison’s diverse catalogue — “The Russians Are Coming…,” “The Thomas Crown Affair,” “Fiddler on the Roof,” “Rollerball,” “A Soldier’s Story” and “The Hurricane,” among others. He takes us through the director’s early days at the CBC in Toronto as well as directing superstars such as Judy Garland and Harry Belafonte in American television. He addresses Jewison’s passion for mentoring the next generations of filmmakers with the Canadian Film Centre.

advertisement

The title of Jewison’s own 2004 autobiography is “This Terrible Business Has Been Good to Me” and he meant it. As Wells writes, “The image that emerges from the thousands of pages of letters, contracts, memos, production schedules, casting notes, draft screenplays and countless other documents is of a director fighting for every frame of his vision.”

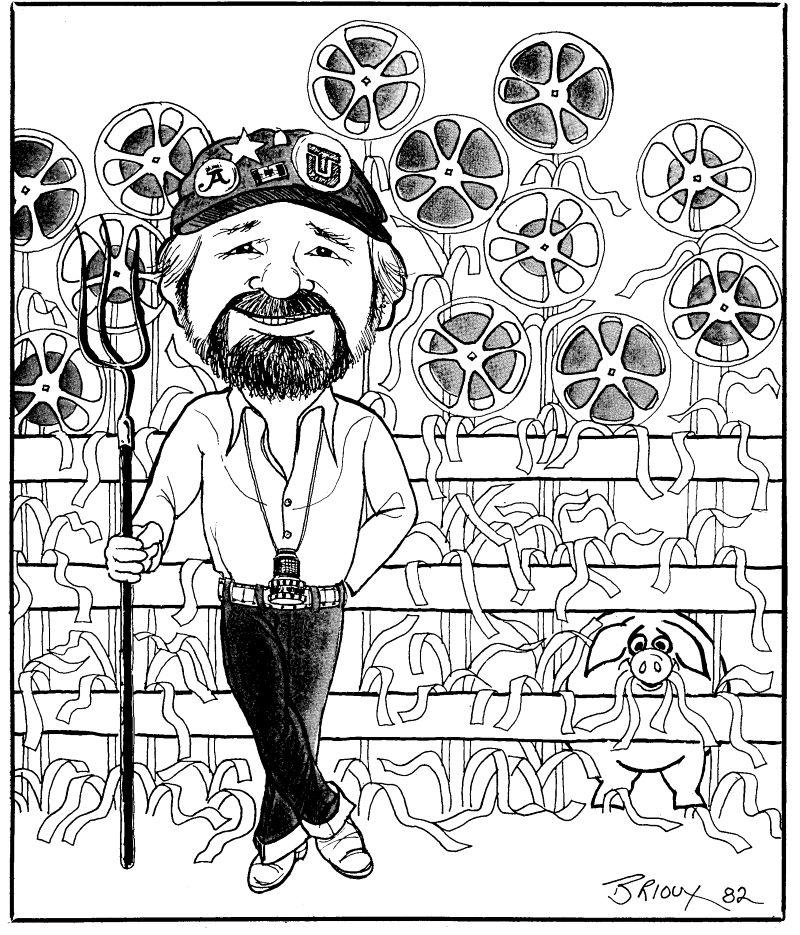

I had the great good fortune over the years to speak with Jewison, including way back in the early ’80s. University of Toronto professor and good friend Gino Matteo, then head of the Cinema Studies program at U of T, invited me to drinks with Jewison at the Park Plaza Hotel. Jewison, by then based on a farm in southern Ontario, had been invited to guest lecture at the university that afternoon and Matteo — knowing I dabbled in caricature — asked me to ‘toon him up for a presentation.

Jewison had just come from directing Burt Reynolds and Goldie Hawn in the romantic comedy “Best Friends.” Reynolds gave a remarkably unmannered performance, and I asked Jewison how he did it. The director apparently took Reynolds aside and told his leading man to save all his tradmark winks and ticks until the end of each take — and then Jewison simply cut them all out.

Later, on another occasion, I eagerly told Jewison I had a 16mm print of his very first feature film, the 1962 Tony Curtis comedy, “40 Pounds of Trouble.”

Jewison’s instructions were blunt: “Burn it!” I never will.

Wells’ rich biography is exhaustively researched and peppered with drama, including head-butts with Hollywood royalty such as Steve McQueen and Faye Dunaway, Sidney Poitier and Rod Steiger, Cher and Al Pacino. Wells gleans and processes every clue from Jewison’s complex and restless personality and then leaves it up to the reader to put the scope of this passionate artist together. Please listen as we go over a few of the highlights in the podcast, and then get to really know Jewison as you make this book your perfect summer read.