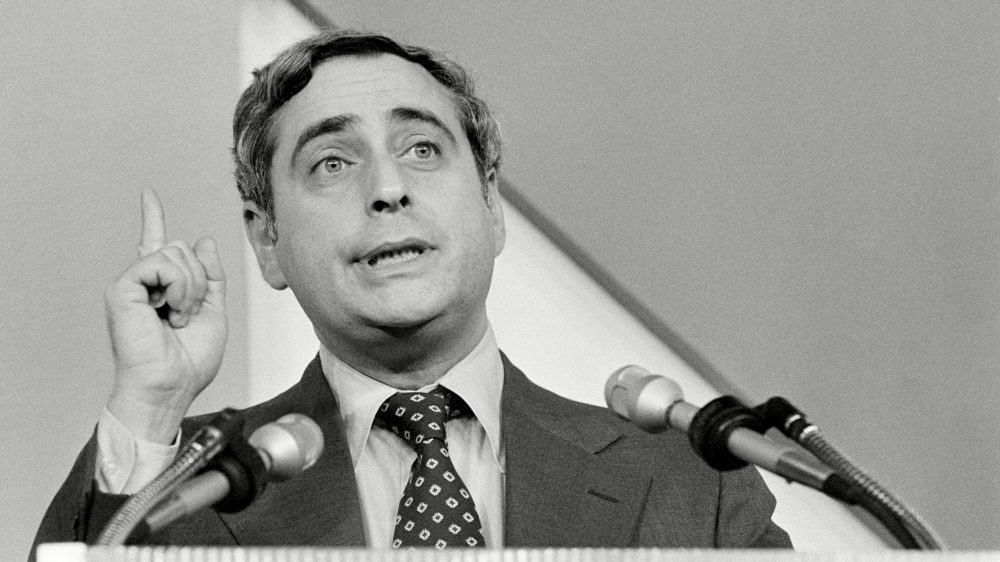

By the time I started covering television in the mid-’80s, one of the titans of the industry was already switching sides — Fred Silverman.

The native New Yorker, who passed away Thursday at 82, did what nobody before or since has ever accomplished — he was the top programming exec at each one of the Big Three networks. This is back when there were only three networks!

Throughout the ’70s, Silverman had his finger on the pulse of what Boomers wanted to watch. His pop culture radar wasn’t unerring, but he helped deliver almost all the TV touchstones Boomers still cherish today. If there was a Mount Rushmore of TV execs, Silverman would be there with Paley, Tinker and Tartikoff.

At CBS, for example, he championed the biggest game changer in TV comedy — All in the Family. Series co-creator Norman Lear tweeted Thursday that “There would be no ALL IN THE FAMILY or MAUDE without Fred Silverman. Bless his every memory.”

He paired it on Saturday nights with The Mary Tyler Moore Show. Maude, M*A*S*H and other hits that followed helped transition CBS out of its rural rut and made it America’s most-watched network.

Silverman was lured to perennial third-place network ABC in 1975 and within two seasons shepherded it from third to first with hits such as Laverne & Shirley, Charlie’s Angeles, Three’s Company, The Love Boat, Fantasy Island and Donny & Marie. He also helped turn miniseries such as Roots and Rich Man, Poor Man into ratings juggernauts. In 1977, Time magazine singled out his ability to pick winners, calling him, “The man with the golden gut.”

advertisement

Part of that knack was knowing how low he could go to draw an audience. Silverman was all in on Battle of the Network Stars, an early celebrity competition series dismissed by critics at the time as little more than a “jiggle show.” That sex sells on television was certainly not a revelation in the late ’70s but Silverman must be given some credit for planting some seeds in the decades-long reality craze to eventually follow.

Battle of the Network Stars

As the man who gave a green light to both All in the Family and Battle of the Network Stars, he also showed that it takes more than vision to successfully program a network; it takes double vision. In terms of taste, you have to know how high and how low you can go.

In 1978, Silverman was again hired by a rival and became president and CEO of NBC. That’s where his hot hand quickly cooled. Silverman commissioned some of the biggest bombs in TV history, including McLean Stevenson’s post-M*A*S*H misfire Hello Larry, inappropriate comedy/variety stinker Pink Lady & Jeff and derailed disaster epic Supertrain. NBC’s biggest star, Johnny Carson, joked at the time that NBC stood for “Nine bombs canceled.”

Had Silverman hung in two years longer, though, he likely would have gone three-for-three in TV network turn-a-rounds. He gave David Letterman his first TV job, albeit as a morning show host (quickly cancelled, but Silverman saw to it that Letterman stayed under contract). He also ordered a trio of sitcom shows that became hits, Diff’rent Strokes, Gimmie a Break and The Facts of Life. Hill Street Blues was an award-winning drama he put on the air; he also laid the groundwork for Cheers and St. Elsewhere.

By 1981, Silverman jumped to the other side of the fence and produced a string of long-running, demos-be-damned hits starring TV icons from the previous decades. Accountants for Andy Griffith (Mattlock), William Conrad (Jake and the Fatman), Carroll O’Conner (In the Heat of the Night) and Dick Van Dyke (Diagnosis Murder) all became big Fred Silverman fans. Silverman also helped produce Alan Thicke’s short-lived late night entry Thicke of the Night.

One of my favourite Silverman stories can be found in Joe Barbera’s 1994 autobiography “My Life in ‘Toons.” The Hanna-Barbera co-founder was trying to sell CBS on a Saturday morning animated series centered around teens and mystery. CBS executives balked when they saw some of the more-frightening concept drawings for the series, emphasizing the horror elements. Silverman was flying to LA and trying to relax by listening to music on earphones when Frank Sinatra’s bit hit, “Strangers in the Night” started playing. By the end of the flight, Silverman had shifted attention away from the teens and onto their dog and had a title for the series, “Scooby-Doo, Where Are You?”

Barbera wrote that Silverman could be “unnerving to work with, in part, because you were always aware that you never quite had his undivided attention.” Barbera recounts a pitch session riddled with interruptions.

“Your life hangs in the balance at these meetings and the guy who’s got all the power is off in a million places at once,” Barbara wrote. Still, three weeks after “this totally frustrating meeting,” Barbera says Silverman called and ordered “Speed Buggy.”

The lesson, said Barbera: “A fraction of Fred Silverman’s attention was worth more than 100 percent of most other people’s.”