In the summer of 2003 I joined several dozen TV critics at a party at Robert Evans house.

It wasn’t like I knew the notorious Hollywood producer, who died Saturday in Beverly Hills at the age of 89. I just happened to be among those shuttled from the Television Critics Association’s hotel that July to a Comedy Central party that took place on the grounds of Evans’ estate.

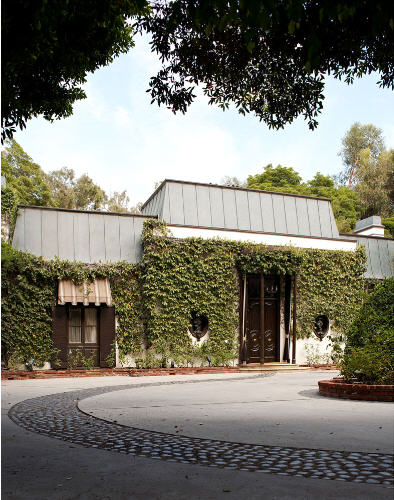

It was a very memorable night. The place was called Woodlands and it was all of that, nestled in a wondrous forest of trees spread over a few private acres in a posh and private part of Beverly Hills.

Evans house was modest in size, almost cottage-like compared to the surrounding mansions in the neighbourhood. It was as styled and unique as its owner, however. Visitors were greeted at the door by Evans butler, “English,” who wore a monocle and spats. The haunting love theme, “What’ll I do?” from one of Evans productions, “The Great Gatsby,” was playing on speakers both inside and outside the house.

Once past the door, you could not help but notice the sheet music to the song on the baby grand, The piano, we were told, was a gift from Evans’ third wife, Ali McGraw, or Elizabeth Taylor, or Gatsby star Mia Farrow – I can’t remember now, but all those names and many more were dropped that night.

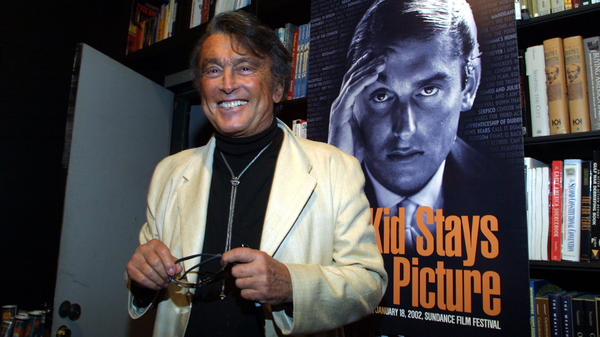

Evans was on the back patio leading out of the house when I first encountered him. He was tanned, charming, and fully recovered from several strokes that had left him unable to walk or speak not that many years earlier. Like Cory Hart, he wore his sunglasses at night.

advertisement

The producer was famous for making and losing a fortune in Hollywood. This party was not an act of generosity; Comedy Central paid Evans to hold it at his estate to promote a short-lived animated comedy based on his life called Kid Notorious. The series turned his Hollywood lifestyle into an animated Osbournes, complete with ‘toon versions of himself, English and his real-life next-door-neighbour, heavy metal guitarist Slash.

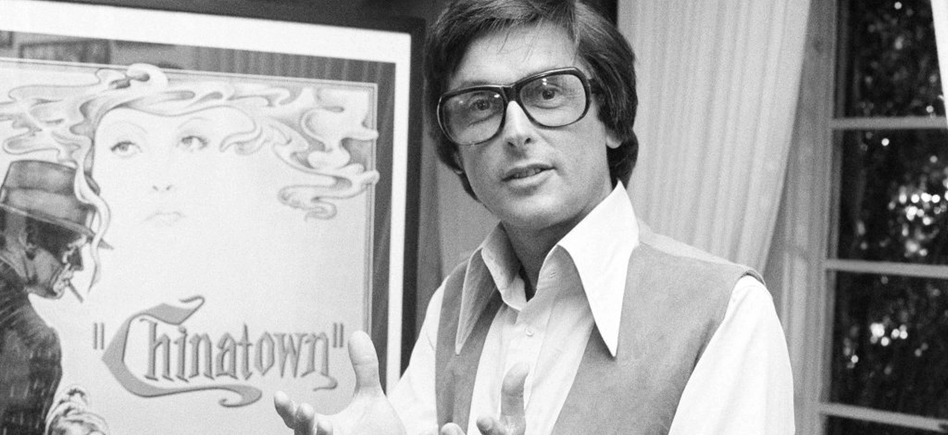

At the steps, I joined in on a conversation between Evans and veteran TV beat legend Ed Bark. Evans had been talking about his incredible run as top gun at Paramount in the ’70s, turning out a string of hits such as “The Godfather,” Chinatown,” “Rosemary’s Baby,” “Love Story “and “Serpico.” Things went south after a couple of big budget independent flops such as “The Cotton Club” and “The Two Jakes.” A cocaine scandal and his tangential association with a murder trial made him an untouchable in the ’80s. That’s when his personal fortune dwindled from $11 million to, by his own count, thirty-seven dollars.

“How are you doing now?” asked Bark.

“I’m in the black,” said Evans. “It’s a little grey, but it’s black.”

He mentioned how fabled Hollywood producer David O Selznick, “died broke in this town.” Then he leaned in, and in that raspy, velvet-y voice, purred, “I’m the richest guy you know.”

It was all very Donald Trump.

Evans also declared to anyone with an audio recorder that night that, of his six wives. McGraw was the love of his life. He went into detail about how Steve McQueen stole her from him. There were photos of her everywhere.

The estate had brightly lit tennis courts with many rows of white tables and chairs set up for an outdoor barbeque. I remember bumping into David Boreanaz and his actress wife Jamie Bergman in line for chicken.

Further out in the yard there was an oval-shaped pool and next to it a pool house-turned-screening room. This was, for me, the greatest part of the estate. Inside, a large flatscreen TV (still kind of a novelty then) played one movie over-and-over again continuously –the Oscar-winning documentary about Evans life entitled, “The Kid Stays in the Picture.” As shameless as it was to run a movie about your own life story for guests, it is one of the best documentaries about a Hollywood narcissist ever.

The walls were covered with photos of Evans with famous people. There were even more covering every inch of the bathrooms. There was Evans with Taylor, Farrah Fawcett, and Michael Jackson – even the Pope. Back in the screening room, there was a small, lit fireplace which had several film trophies on a narrow mantle.

At the back of the room were seven large, black leather Barcaloungers. Next to Evans’ middle chair was an old fashioned black telephone with buttons connecting him to the projection booth (right behind the chairs), the kitchen and his bedroom.

We were told early on that two rooms were strictly off limits – Evans bedroom and the projection booth. Naturally, I had to get into the projection booth. (The bedroom was even easier to crash later.)

I told English of my own 16mm film collection and how I projected films at various industry events back in Toronto. He snuck me inside the booth, showing off the two, cinema sized, 35mm carbon arc projectors. Jack Nicholson was a frequent guest, he told me. The other night the Oscar-winner had been over watching an early Evans’ production — “Harold & Maude” – for the umpteenth time.

Then English surprised me with a souvenir – one of the carbon sticks used to produce the intense light inside the projector. It was still smudged from being burned to make the light the night before.

I still have it, and wonder if it was missed four days later when Evans’ beloved screening room BURNED TO THE GROUND. Fortunately, the house and the rest of the grounds were saved.

Evans was still reeling – pardon the pun – from the loss of his favourite spot when I spoke with him the following spring. (I was then at The Toronto Sun and interviewing the producer on the phone about the Canadian premiere of Kid Notorious.)

“It was like losing my right arm,” Evans said of his flamed out film fortress. He had lived on the property since 1966. “It was the drop-in centre of everybody coming for films.”

Evans told me he had to move screenings of his documentary into his bedroom. He claimed he had “20, 30 people a night” crammed into the room, the lucky ones getting a corner of his King sized mattress. “I’ve had everybody from Jude Law to Daryl Hannah to Jack Nicholson lying on my bed watching it.”

Hard to believe there was room. The bed, the night I saw it, was littered with everything you might find on a messy desk, including phones, folders, books and scripts and even food and drinks.

Once Evans had my number he kept calling. He’d call, put you on hold, take other calls — even for a typist from Canada, he put on a show. He’d come back on the phone and tell you he’d just sold Kid Notorious to half of Europe — and to please print that.

When Evans hit rock bottom, he was forced to sell the house to Japanese businessmen. The move plunged him into a deep depression. His pal, Nicholson, flew to Japan, bought the place back, and surprised Evans with the keys.

There was the great, Hollywood love story — not Jack and Evans, Evans and the house. I hope he left it to Nicholson.