I was asked on my first of several interviews upon hearing the news of Matthew Perry’s passing if there were any signs he would leave us so young.

There were, of course, nothing but signs. There have been actors I’ve spoken with in the past who have died even younger, such as Cory Monteith from Glee, who you wish you could have helped. It is a ridiculous wish, especially in Perry’s case. Sometimes you can never escape your own fate, no matter how famous you are, even when the end seems so utterly random.

Matthew Perry died Saturday, October 28, at home in Los Angeles. He was found unresponsive in his hot tub by his assistant. He was 54.

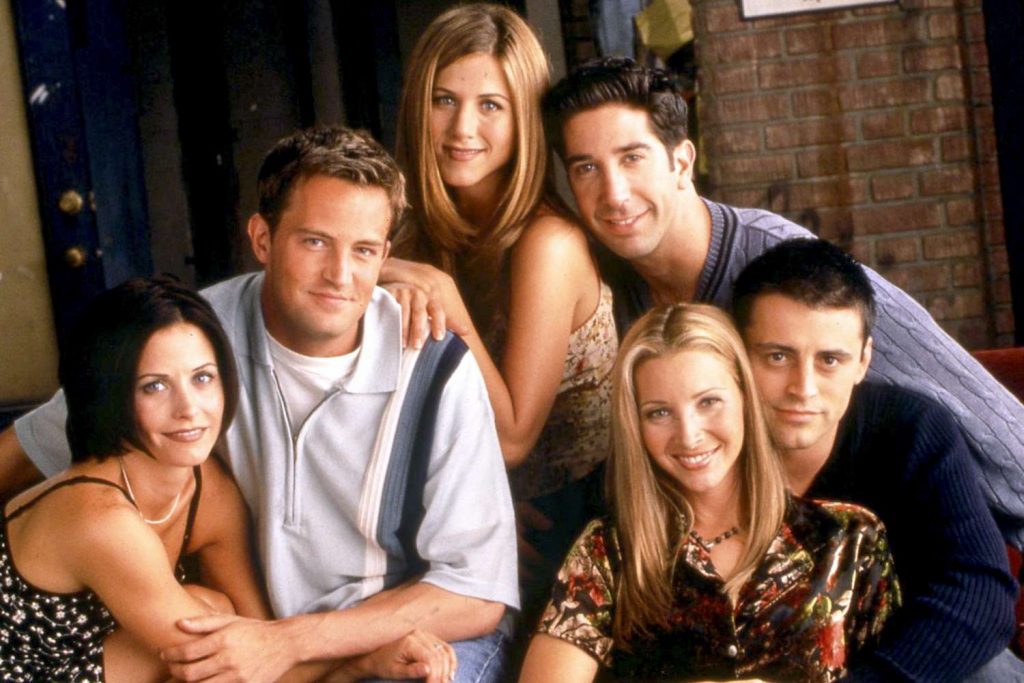

He had just turned 24 when he was catapulted to fame as Chandler Bing on Friends. I first interviewed him a few days before the series premiered in September of 1994. Perry was in Toronto and was a guest on Global’s afternoon series Entertainment Desk. I worked for TV Guide Canada at the time, and host Bob McAdorey had me on every Friday to preview the coming week on TV. Instead of bumping me altogether with Perry as the guest, generous Bob asked me to stay when I arrived at the station and help him interview the young actor.

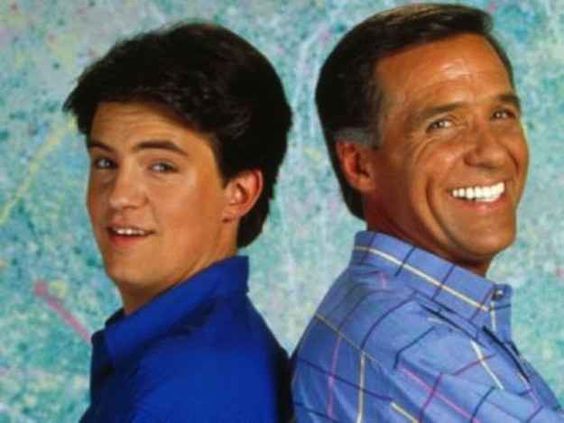

I was certainly aware that the series was already forecast to be an enormous hit, although things don’t always turn out that way (see Perry’s next NBC series, Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip). Perry had been part of three or four duds already, so his head wasn’t completely turned at this stage. He’d been a tennis brat before that, ranked competitively in Canada as a teenager. His father, John Bennett Perry, had achieved some notoriety in TV commercials as the Old Spice aftershave man. His mom Suzanne Perry, who raised him, worked for former Canadian prime Minister Pierre Trudeau. Perry went to school growing up in Ottawa with Pierre’s son, Justin, the current PM. His stepdad was Canadian-American news anchor and Dateline NBC correspondent Keith Morrison.

From an early age, therefore, Perry was no stranger to fame.

advertisement

Just not on this scale. Friends‘ director Jim Burrows took the six cast members to Vegas prior to the premiere and told them that their lives would soon change to the degree that none of them would ever be able to wander anonymously around Las Vegas or anywhere else again.

I found Perry relaxed and taking things in stride at the Global taping. He acknowledged he’d been on bombs before, joking that he and Jennifer Aniston, Matt LeBlanc, David Schwimmer, Lisa Kudrow and Courteney Cox had suffered through “more failed shows than Robert Urich.”

Perry’s forgotten flops included shows such as Sydney, Boys will be Boys, Home Free and the aptly named Second Chance. He was almost at the point of giving up and had in fact started trying to write his own show. NBC showed interest, but backed out, as he was told, when another show came along too similar to his that they liked better. That turned out to be Friends.

The creators of Friends, Marta Kauffman, David Crane and Kevin Bright, remembered Perry from an episode he did of their previous series, the quirky HBO series Dream On. “It’s like a gift from somewhere that I’m working with them,” said Perry. “They took all these actors who were good on bad shows and put them on a good show.”

Perry’s world had changed a year later when the actor returned to Toronto to do more publicity for the series, an instant smash on both NBC and Global in Canada. Global had put Perry in a decent downtown Toronto hotel. The avid Toronto Blue Jays fan balked and insisted he be relocated to a posh suite overlooking the ball diamond at the city’s SkyDome hotel. That was quickly arranged. Perry was pleased.

“Some people would love to have a room overlooking the Riviera,” he told me. “For me, this is it.”

At the time, Perry’s California license plate back home on his Porsche in California read “092 JAYS.” The team won their first World Series title in 1992.

The series was hailed as a standout in the New York Times, making the cover of the Rolling Stone, Entertainment Weekly and People. Oprah flew the entire cast up to Chicago for a taping that Perry sheepishly described as “a Friends love-in.” By season’s end, the series was pushing NBC’s ER for first-place in the ratings.

In our interview, Perry downplayed his contribution, suggesting Chandler Bing was basically a “slightly exaggerated form of me on all levels.” That, combined with a lot of TV experience for one so young, helped him become the zinger of the series, the closer they brought in to get the save. Perry’s timing and delivery and eye rolls were Michael J. Fox good.

With fame, came fortune. The six actors were smart enough to band together at contract time. Perry, by Season Two, was confident enough to buy a house in the Hollywood Hills.

“It’s kind of a sitcom rule,” he said. “If you go to a second season, you must buy a house.”

Much of our second interview was conducted over steak sandwiches at what was the Inn on the Park hotel in Toronto. Perry acknowledged that life was good. That the cast had all been flooded with movie offers. He was also living out hockey fantasies, skating with the likes of Michael J. Fox and Alan Thicke in celebrity leagues and shooting NHL promo spots for playoff games on Fox.

As Perry himself chronicled in his 2022 autobiography, “Friends, Lovers and the Big Terrible Thing,” there was a price to pay for so much fame. He was often overwhelmed by demons and addictions that dogged him throughout his career. By the time he was 49, he calculated that he had spent half his adult life in treatment centres and sober living facilities. Viewers who watched the Friends reunion special in 2021 saw Perry struggle through that taping. A friend who listened to Perry’s audio version of his bestselling book said she heard the voice of a man who clearly was not well.

On those early interviews, Perry in his mid-20s hid those addictions well from reporters. He seemed witty, gracious, charming and engaged.

By the time Friends ended its run in 2004, however, access to the cast became much more limited. Perry and the others sat on director chairs down on the floor of their Warner Bros. soundstage when TV critics gathered for the show’s final TCA press conference. Once the session wrapped, the cast was whisked away and the press stayed penned in the bleachers.

By the time I caught up with Perry in January of 2007 he was one of the headliners of Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip. That star-packed series was writer-producer Aaron Sorkin’s take on a behind-the-scenes of a Saturday Night Live-like series. It was billed as can’t miss, but by the time TCA reporters were invited to the set in mid-season, the show was already in trouble. Besides Perry, who played a comedy writer, the series also starred Bradley Whitford, Amanda Peet, Steven Webber, D.L. Hughley, Sarah Paulson, Nate Corddry and Timothy Busfield.

Everybody put on a brave face, but my strongest memory of the occasion was of Perry sipping back cans of Jolt Cola as he tried to help talk up interest in the series.

A few years later I spoke with Perry at another TCA press tour session, this time for NBC’s sportscaster-themes sitcom Go On (2012-13). He had already weathered a few more flops. NBC hosted an event at what was then the abandoned Trader Vic’s lounge at the Beverly Hilton Hotel. Perry was among many stars in the dark, crowded event space. He was candid about his struggles but gracious and friendly and focused on promoting the series at hand. It was probably our best conversation. Perry could be a true strait shooter. He was smart, witty, self deprecating but also willing to talk past the charm offensive to make a connection and to get a message across.

“I gravitate towards sort of broken characters who try to be better people,” he had said earlier that day at the NBC press conference. He was playing a Jim Rome-like sports radio broadcaster on Go On. “This guy has had some very dramatic things happen to him, and he’s in denial when you meet him. So it’s a sort of built-in excuse to be really funny, much like this answer was.”

Perry suggested a few other characters he had played, including one or two he helped script, did not connect with viewers because they simply weren’t nice enough. “Why,” he was asked, “do people want you to be nicer than you want you to be?”

“I’ve been asking that question for many years,” he snapped back. “I don’t know why that is. But you certainly want to play a guy that people can get behind and root for, and I think that this character does have that.”

Perry continued to search for his next big Chandler Bing role. Friends, he eventually realized, was once in a lifetime. The series had terrific chemistry, writing, directing and acting. “So a little bit of magic happened there,” he said. “And you never know when and how that’s going to happen. All you have ‑‑ you just want to surround yourself with funny, talented people.”

At 25, back when I interviewed him in Toronto, Perry already understood that all of this could go away very, very fast. “In three days,” he said, glancing down at the magazine on the table before him, “we won’t be on the cover of Rolling Stone magazine anymore, you know?”

In some ways, Perry’s next hit was his original one — Friends. Few shows ever connect so powerfully with the generation born 20 or 30 years after a series left the air. Friends remains a big moneymaker for Warners, a sought-after jewel among streaming services. All 10 seasons, for example, now stream exclusively in Canada on Crave and in the US on Max.

His legacy will be one of laughter for fans of the series of all ages. While the reruns will be there for you for many years, his life story will also remain a serious caution about the health risks of long-term addiction even in cases where sobriety is achieved.

His premature death, however, is just very sad. You want your Friends to all have happy endings. Perry’s death at 54 is just, ironically, so sobering. Condolences to his family, friends and many fans.