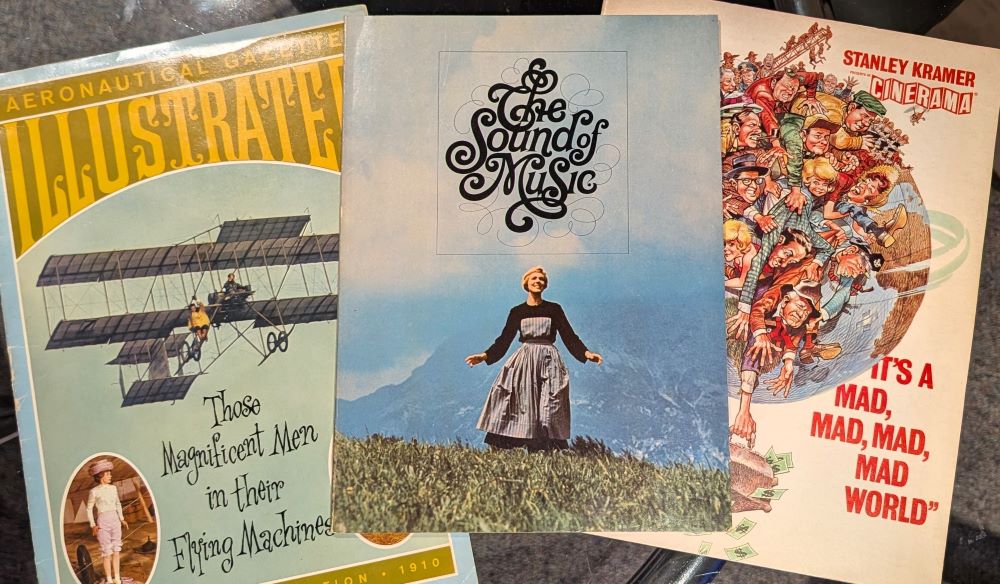

When the folks at Zoomer magazine asked me to write a feature celebrating “The Sound of Music” at 60, I immediately reached for a copy I have of the original roadshow screening of the movie. (You can read that story here at Everything Zoomer).

Movie studios used to publish these lavish, hard cover magazine-style mementos to promote their biggest releases. When “The Sound of Music” premieres on March 2, 1965, 20th Century Fox put out the 50 page booklet seen in the above photo. Additional copies of the souvenir book, it says on the inside back cover, could be ordered at the time, by mailing one dollar to National Publishers, Inc.

This was all part of the amazing live movie going experience at the time. Not all the ballyhoo worked. The same studio nearly went under a few years earlier when “Cleopatra,” starring Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, was snake bit at the box office. Critics were not kind to “The Sound of Music either. Judith Crist at the New York Herald Tribune called it “icky sticky.” Pauline Kael in McCall’s dismissed it as “the sugar-coated lie people want to eat.” Even Andrew’s costar, Christopher Plummer, cheekily referred to it as “The Sound of Mucus.”

It was long, too, at three hours and ten minutes. Released twenty years after the end of World War II, this lilting musical seemed a bit odd, to say the least, against the background of Nazi horrors.

None of this deterred audiences from lining up to see it. It was the first feature film release to earn over one hundred million dollars. In Toronto, The feature played at Toronto’s Eglinton theatre for 146 consecutive weeks. Fox went so far as to renovate the art deco cinema, which originally opened in 1936. A new screen, new projectors, carpeting and wider, more comfortable seats were installed. The orchestra was reduced from 1100 to 800 seats with an additional 300 (down from 500) in the balcony.

Back then, intro or “overture” and “exit” music played with those words often projected onto the curtains before the picture started. There was a prolonged intermission which triggered stampedes to the washrooms and concession stands. People would climb mountains of popcorn and ford every, well, you get the idea.

advertisement

Despite the long length, people would go and see this movie two or three times. It was the ultimate family film, and a year-and-a-half removed from the Kennedy assassination, there was comfort in seeing Julie Andrews twirl, sing, dance and go all Bavarian. Even the seven year olds in the audience, like me, could identify with the various von Trapp children. Nobody should have to words to “Do-Ra-Mi” in their head for 60 years, but that is what happened.

By 1967, “The Sound of Music” might have seemed out of touch with the restless, era-changing, “Summer of Love” movements of the time. Even in 1965, released prior to The Beatles’ second movie, “Help!”, it caught one of the last waves of middle-of-the-road mom and pop-ism. A “Sound of Music II” would have found the von Trapp grandchildren backing Joe Cocker or Hendrix at Woodstock.

Certainly the film was not made for today’s attention spans. Even when it finally premiered on television in 1976, fetching a record US$15 million from ABC for a single broadcast, 30 minutes was cut out to made room for commercials. Nobody seemed to mind then; now it would be cut down to Tiktok length.

Still, there was something about the relatively languid storytelling that worked, especially when it was experienced with over a thousand other people. There were several pitches from Conan O’Brien and others at the recent Oscars, urging TV viewers to get off their couches and go to the cinemas.

Big movies need big spaces. In 1965, “The Sound of Music” filled movie theatres in a very different way than today’s hyper-kinetic super hero blockbusters. There were no computer generated effects, no Dolby sound. It was shot on location, taking advantage of the technological advances of the day, but it still came down to casting, music, story, and being the right picture at the right time. The potential sure seems to be there to find a modern property that would bring people split into so many divisions together again under one roof. As Oscar Hammerstein might ask, “How do you hold a moonbeam in your hand?”