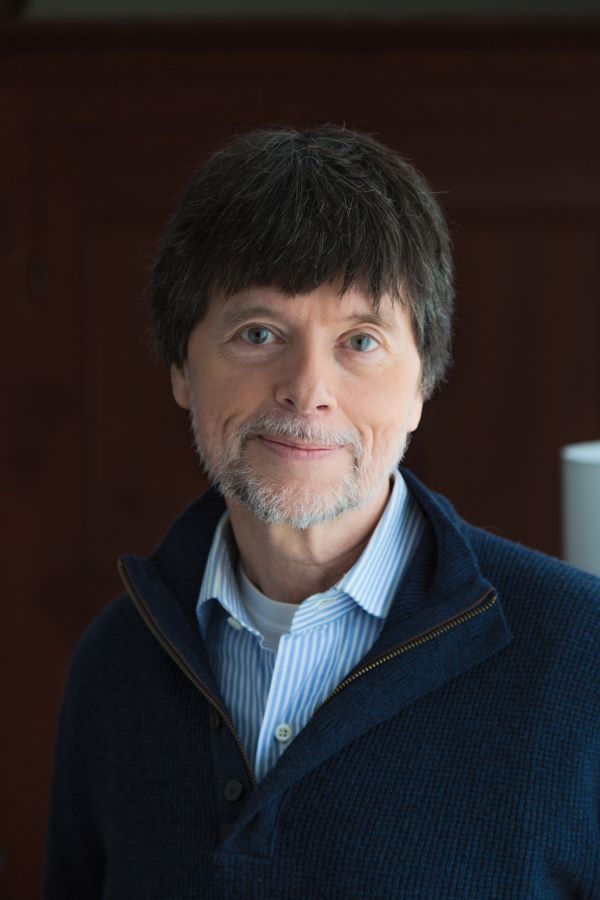

In some ways, Ken Burns takes on his toughest opponent with “Muhammad Ali.” His four-part, eight-hour documentary series about the late, great heavyweight champion and civil rights icon premieres Sunday and airs over four nights through September 22 on PBS.

It is, in Burns’ words, a documentary that is “soup to nuts comprehensive in terms of the arc of his life,” from his birth in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1942 to his death from Parkinson’s in 2016. It also, surprisingly and like Ali himself, shines in the quietest moments.

That sets it apart from other Ali documentaries, of which there are many. “When We Were Kings” (1996) looks mainly at Ali’s famous “Rumble in the Jungle” against then undefeated heavyweight champion George Foreman in 1974. That film benefits from some astute commentary from ringside observers George Plimpton and Norman Mailer, both still alive when this doc was made. It took director Leon Gast 22 years to edit and finance and won the Academy Award for Best Documentary.

One of the more recent, “Ali & Cavett: The Tale of the Tape” (2018), explores the unique relationship between the fighter and TV talk show host Dick Cavett. Ali appeared on Cavett’s show at least a dozen times and the two became unlikely friends.

“Facing Ali” (2009), made by Canadian producer Derik Murray, is told from the perspective of ten of Ali’s greatest opponents. Joe Frazier, George Forman, Henry Cooper, Leon Spinks, Larry Holmes and Ken Norton are interviewed, but the most poignant and articulate, in my view, is Canadian champion George Chuvalo, who Ali taunted as “The Washerwoman.” Chuvalo fought Ali twice, before and after Ali’s ring exhile in the late ’60s, and took him the distance each time.

Here’s where taking on Ali exposed Burns to lefts and rights and plenty of jabs. Because there have been so many documentaries on Ali, some fans are going to quibble about what has been left out. Go ahead and quibble, says Burns.

advertisement

“I always am happy to hear that people are pissed off because I’ve left something out,” he told me on the phone from his office in New Hampshire last month, “because they’re not saying an 18-and-a-half hour film about baseball, or an eight-hour film about Muhammad Ali, is boring.”

Burns adheres to a strict “subtractive” approach to documentary filmmaking. He referred me to the 1984 movie “Amadeus,” where the lesson for Mozart’s musical rival was never cram in too many notes.

“The law of storytelling doesn’t permit you to put everything in,” says Burns. “The law of telephone books does. No one reads the telephone book.”

Burns, who always seems to have several projects on the go at once, worked seven years on “Muhammad Ali.” As he tells me in an article now up at EverythingZoomer on-line, he’s grateful PBS allows him to take all the time he needs on these projects.

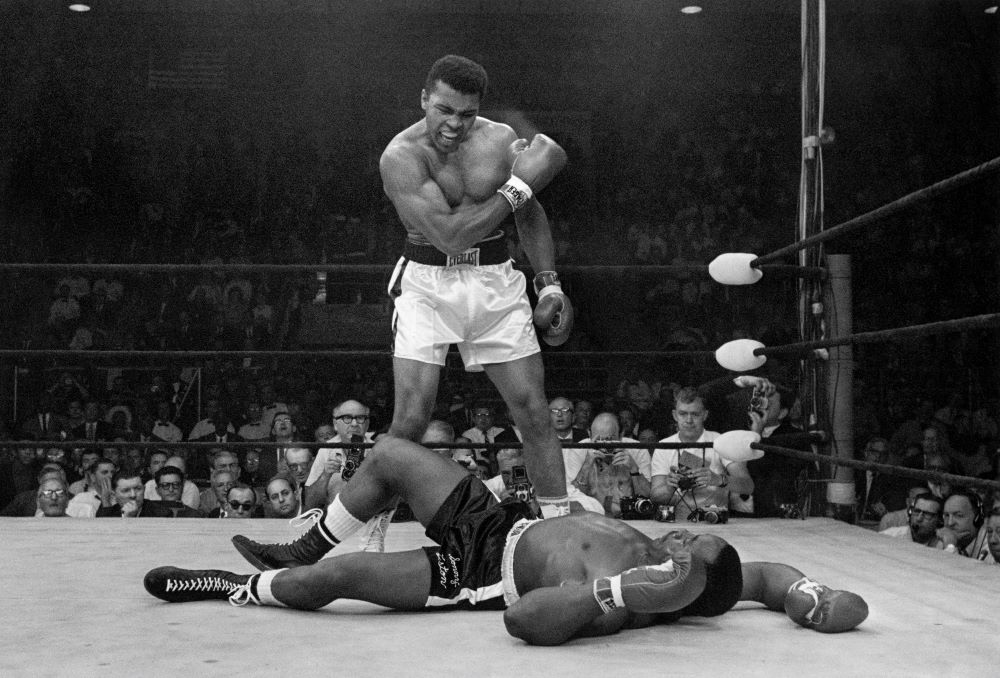

As a result, on “Muhammad Ali,” he was able to hunt down and acquire rights to (and raise funds for) some exceptionally crisp footage of Ali’s most memorable encounters, including the bouts against Frazier and Foreman. Best of all, the fight many boxing insiders consider Ali’s masterpiece, his 1966 match against Cleveland “Big Cat” Williams, brings you ringside as it looks like it was shot yesterday.

While the fight scenes and commentary, especially from boxing writer Robert Lipyte and former heavyweight champion Michael Bentt, bring perspective to the story, it is Ali himself who shines throughout. As Burns points out, for all his celebrated ballyhoo in and out of the ring, it is the boxer in his quietest moments who is most fascinating.

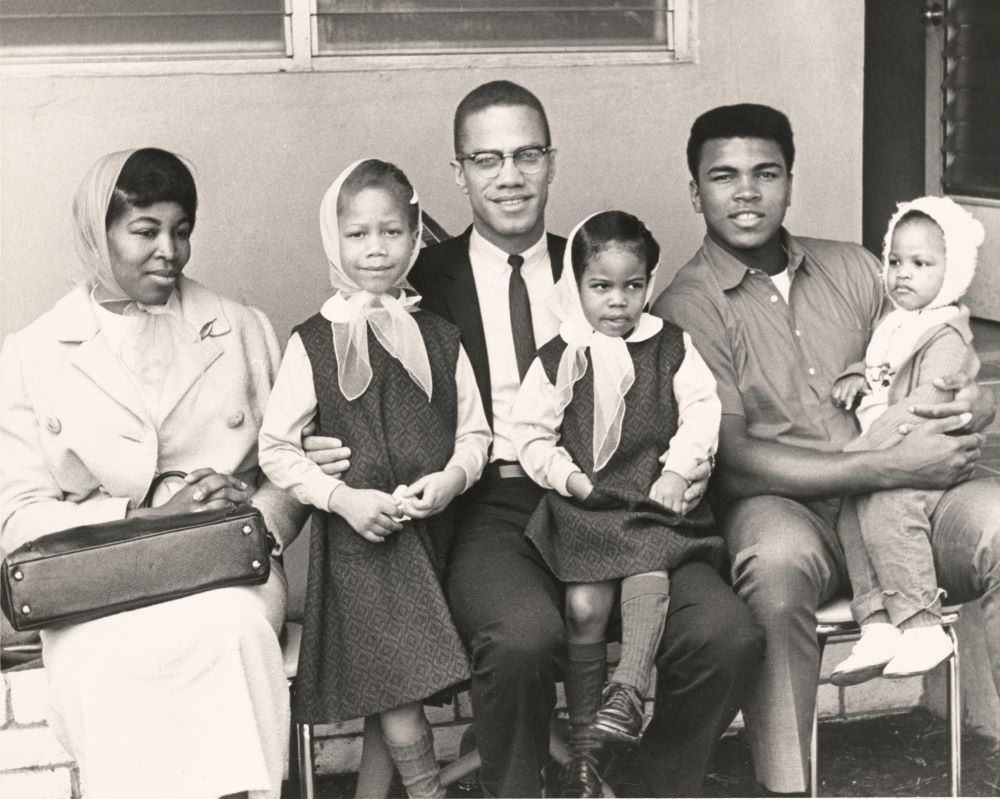

This is especially true in the extraordinary sequence where Ali is reached for comment immediately after it was announced that the Supreme Court had just liberated him — on a technicality — from a five year prison sentence for refusing the draft.

“You would expect a crowing, bragging Ali,” says Burns. Instead, this young man in his twenties quietly says, as Burns’ paraphrases, “‘I don’t know who’s going to be assassinated tonight. I don’t know who’s going to have equality or justice denied them,’ and he’s really taking in all of the previous, 350 years and all of the next 50 years of racial descrimination on this continent and it’s very beautiful to me.”

Ali shows a similar thoughtful side after losing epic battles to Joe Frazier and Ken Norton. He’s humble, collected and even gracious. It’s a voice you seldom hear nowadays when losses, especially political ones, are rejected and anger and defiance seem like the only answer.

Ali’s Parkinson’s eventually robbed him of all speech, which seems cruel and punative, until you step back and consider those quieter moments earlier in his ring career. As Burns says, with Ali, “there was something about his silence; he gained even more power.”

The four-part, eight-hour documentary is directed by Burns and written and co-directed by his daughter Sarah Burns and David McMahon.