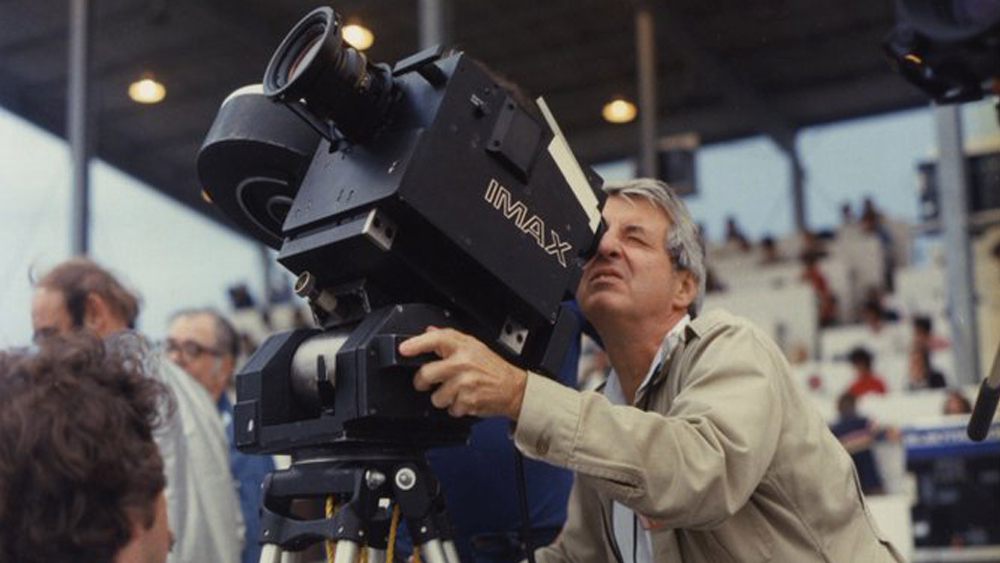

Canadian filmmaker and IMAX co-inventor Graeme Ferguson passed away May 8 at 91 at his home in the heart of Ontario’s cottage country. He made a film that had a great impact on this writer as a young teenager — “North of Superior.”

Mr. Ferguson career in television reached back into the ’50s and included stints in India and New York. He was already a cinematographer-writer-director by the time he worked on a series briefly hosted by Ernie Kovacs, Silents, Please (1960-62). That homage to Hollywood’s roots extended to profiles of film icons Valentino, Marilyn Monroe and others. He later dabbled in scripted features, co-writing and directing an obscure political comedy called “The Virgin President” released in 1968.

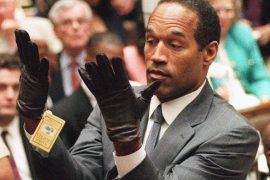

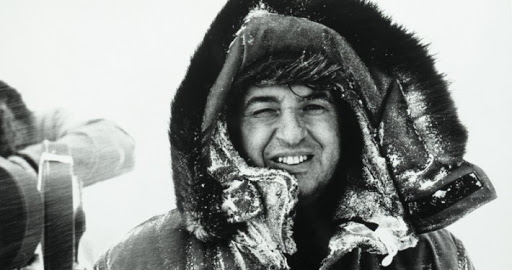

Prior to that, he was in on an experimental film made for Montreal’s Expo ’67 called “Polar Life.” It was a multi-screen, multi-projector effort shown to viewers watching from a central, rotating turntable. After burning through hundreds of projector bulbs, Ferguson and collaborator Roman Kroitor started wondering how they might recreate that same experience on one giant screen using one projector.

In 1967, they founded Imax Corporation along with high school friend and businessman Robert Kerr and engineer William Shaw. Once they figured out the projector system and theatre configuration, they tested it out at Expo ’70 in Osaka, Japan with a film called “Tiger Child.”

Fifty years ago this spring, in 1971, Ontario Place opened with Cinesphere as its iconic screening sphere of the future. The big, round ball was as if Buckminster Fuller’s American pavillion at Expo ’67 and Hollywood’s Cinerama Dome on Sunset Boulevard had a kid.

Cinesphere was designed by architect Eberhard Zeidler, also responsible for the look of the Toronto Eaton Centre. This was way before stadium seating became the norm in cinemas. Stepping into the place was a mind-blowing adventure for me at 14; you made your way through a narrow, curved corridor of dark blue carpeting and emerged at the mid-point of an enormous space where the row of seats seemed raked so steep you might fall into the screen — which was six stories high. Behind it were 80 or so speakers.

advertisement

As somebody who threaded a 16mm projector at home, I scrambled up to the back row and peered into the projection booth. There a 70mm projector was turned sideways and the film sat horizontally on giant, stainless steel platters. That turned the image 90 degrees, expanding the surface image of the film frame ten times it’s normal size in a regular, 35mm projections.

Ferguson’s film,”North of Superior,” was the perfect featurette to launch Imax at Ontario Place. It did not walk you up nearby Yonge Street or other Toronto landmarks. Instead it emersed you into the majesty and power of the Ontario north, plunking you straight into a white water canoe adventure and a raging forest fire.

Four years ago, in 2017, “North of Superior” was re-presented at Cinesphere, the house Ferguson helped build. At 88, his passion for Imax and Ontario Place remained vibrant.

Part of the reason the film resonates so much for me is that, as a teenager, I worked as a busboy at a restaurant on the West Island of Ontario Place for three summers. The Blockhouse, as it was called, faced east, and over the course of many months, I literally watched the CN Tower go up.

Revisiting a film I probably saw 50 times in the early ’70s was exhilarating. I’ll never forget that first joyride of feeling like the entire audience was banking like one big airplane as the movie took off with a sweeping, fixed wing ride over unspoiled forests and streams in northern Ontario.

Sporting his Order of Canada pin, Ferguson explained how the movie and the theatre were more or less accidentally made for each other. The province had commissioned the geodesic dome — modeled, as all of Ontario Place was, on successes at Expo ’67 — without knowing what to put in it. Meanwhile, the Imax team was searching for a theatre big enough to showcase their new, large-format invention.

Ferguson called a friend, Christopher Chapman (a colleague from their Expo days and director of the landmark featurette “A Place to Stand”) and it was Chapman who suggested IMAX and the province might have a mutual interest.

I spoke with Ferguson after the screening and asked a few questions. The film ends with the camera in the middle of a raging forest fire. Ferguson says his crew “waited all summer” for one to break out and finally took the logger’s suggestion that he record a controlled fire. The sequence looks scary, but Ferguson says no one was really at risk as fire crews were prepared and surrounded the site.

I also wondered about the camera placement for the soaring opening sequence. My guess was that it was mounted under the plane. There are a few moments when the point of view seems to skim the tree tops. Ferguson says it was mounted in the nose cone of the airplane — although the pilot flew so close to the ground they had to pick a few pine cones later off the bottom of the aircraft.

The other Imax theatre in Toronto at that time, as I recall, was the McLaughlin Palentarum next to the Royal Ontario Museum. Both the Planetarium and Ontario Place sit either empty or underused today. Are they victims of an analogue age? Where are the visionaries of today to emerse us in a digital, 3-D world of sight and sound — and do it at the speed things came together in the ’60s?

Graeme Ferguson showed that all it takes is vision. Surely somebody out there is dreaming of going out to the movies again someday, and getting people there by turning the whole deal sideways.

One last note: Ferguson’s wife Phyllis predeceased him by eight weeks. The two will be interred together in Thunder Bay, Ontario — north of superior.